do you feel guilty

By Nicholas McCoy

Originally written for The Thunderword.

Video games are more than just an easy source of entertainment; they’re a source of narrative depth that deserves closer analysis.

There’s a long established history of literary analysis and film analysis. People look at the themes of a work, at the emotional efficacy, at the story it tells and the metaphors it uses. The authorial (or directorial) intent is examined.

I don’t see that process happening as often for video games and I think that’s a shame—because interactive fiction provides avenues for effective storytelling that aren’t available elsewhere.

One of those avenues for storytelling is the creation of user complicity. That is, making the consumer of a story personally responsible for the actions that occur. When a character in a horror movie opens that door you know they shouldn’t open, it’s dramatic but also distant. When you play a video game, you often have to personally initiate the action that opens the (sometimes literal) door to hell.

The story may not give you the option to ignore the door—much as a protagonist in a movie may have no choice but to move forward—but unlike in a movie or a book, you choose when it opens. You become complicit, and subconsciously responsible, for the fear you feel later.

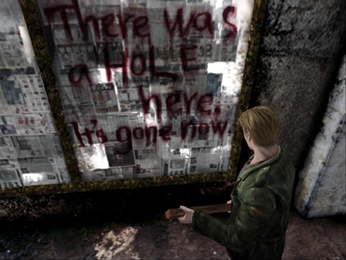

One game I’ve played that I can never stop analyzing is Silent Hill 2. Silent Hill 2, released in 2001, is a very graphic, violent survival horror game. It also has the kind of subtext and emotional effect that many (if not most) novels and movies never achieve.

The story follows James, who believes he has received a letter from his dead wife telling him to find her in the city of Silent Hill. There he encounters horrifying monsters, some of which try to attack him and others that attack each other. The game, despite its context, doesn’t focus on combat. Players are more likely to avoid injury and survive if they simply run away instead of trying to violently engage the game’s creatures.

It is also implied during the game that what James sees is not reliable; in the beginning of the game, the character is confronted with and forced to kill one of the monsters. If the player returns to the site later, they’ll find police crime scene tape blocking off the scene.

Silent Hill 2 is a story about the destructive nature of guilt. The protagonist, James, is consumed by anguish over his complicity in the death of his wife. The endings of the game reflect the possible outcomes that guilt can take; he can leave it, and Silent Hill, behind. He can be consumed by it, committing suicide out of guilt and grief. Or he can suppress it, leaving Silent Hill but not the guilt or its hell-narrative behind.

The player’s actions as James, and how he treats himself, influence the ending. If James heals himself immediately after injury, he’s more likely to leave Silent Hill behind—he’s showing a desire for self-preservation rather than punishment. If the player chooses to have James walk around injured (and presumably in pain), the suicidal ending becomes more likely.

When I play Silent Hill, and even non-horror video games, I find that by initiating the actions that result in a given storyline unfolding, they hold a certain kind of power over me. What I’m seeing isn’t just the results of what a character I sympathize with has done; often, in a video game, it’s the result of what I’ve done, for better or worse. It taps into my brain more directly than passively experiencing something in a movie or book does.

I find playing a game more like reading a book than watching a movie; when I read a book, I actively choose to turn the page or read the next section. A video game increases that complicity while also giving the director increased access to evocative techniques often used in film.

Video games have the unique ability to flesh out possible divergent story lines and the consequences of actions in way other media do not. As video games continue to boom, it’s important to begin to place them in a more analytical context.