How to build efficient systems of

spreadsheets to save time, get promoted and have extra time for vacation

An Excel book that takes you from the beginning

theories of how to construct efficient systems of spreadsheets towards the

Beautiful Excel infinity at the other end

By Michael “Excel Is Fun!” Girvin

Warning, because this book is free, I

could not afford an editor. So you will have to put up with the occasional

spelling/grammatical error. If you find any kind of error, please e-mail me at

mgirvin@highline.edu.

Dedication:

This book is dedicated to Dennis “Big D” Ho, my step-son,

because he loves books so much!

Table of

Contents

Introduction. 4

What

Is Excel?. 5

Rows,

Columns, Cells, Range Of Cells. 6

Worksheet,

Sheet Tab, Workbook. 7

Menus

And The Alt Key. 9

Toolbars. 10

Save

As is different than Save. 10

Two

Magic Symbols In Excel 11

Math. 17

Formulas. 21

Functions. 26

Cell

References. 36

Assumption

Tables/Sheets. 51

Cell

Formatting. 61

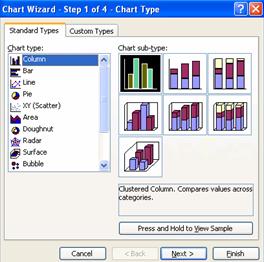

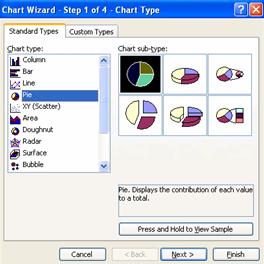

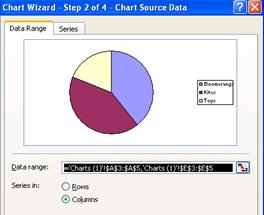

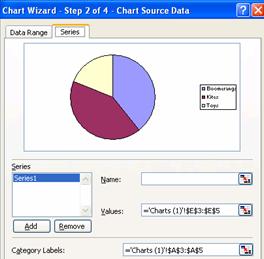

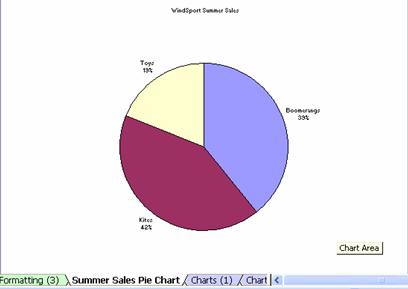

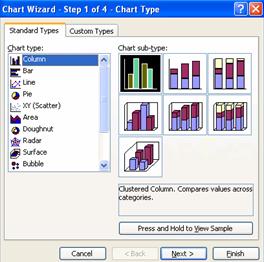

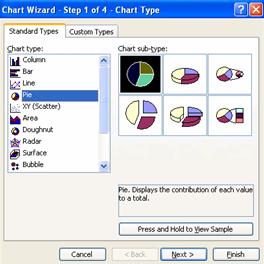

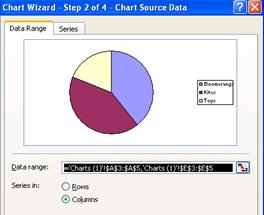

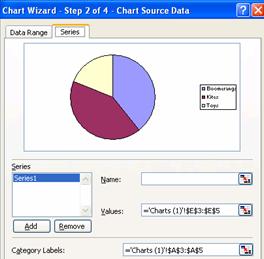

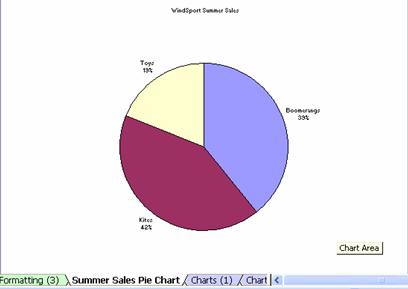

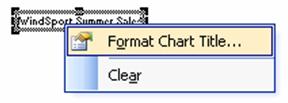

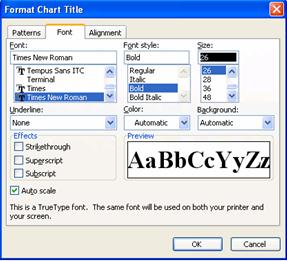

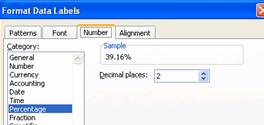

Charts. 85

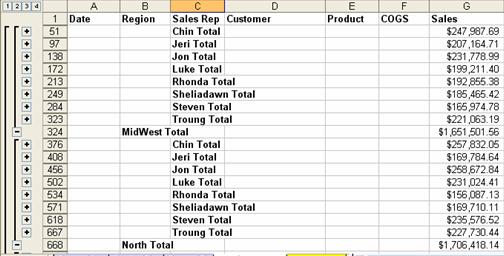

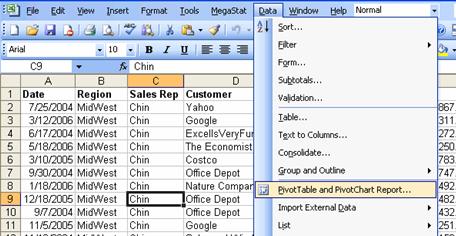

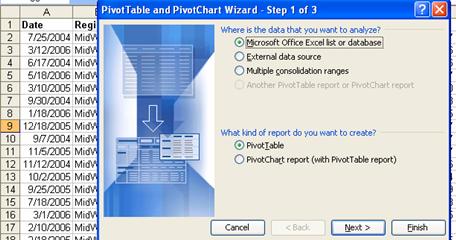

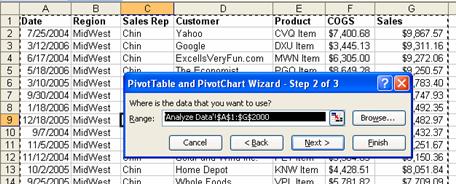

Analyze

Data. 95

Conclusion: 103

Excel is Fun! Why? Because your

efficient use of Excel can turn a three hour payroll calculating chore or a

five hour reporting task into a five minute breeze. You save a lot of time.

That time adds up to extra time for your more enjoyable endeavors in life such

as vacations! In addition, your bosses and employees will notice that you are

efficient and can produce professional looking reports that impress. This of

course leads to promotion more quickly. Still, further, your knowledgeable and

efficient use of Excel can land you a job during an interview. Employers are

like dry sponges ready to soak up any job candidate that can make their entity more

efficient with Excel skills! Save time?, get promoted?, get the job?, and have

more time for vacation? – That sounds like a great skill to have!

In the working world, almost

everyone is required to use Excel. Amongst the people who are required to use

it, very few know how to use it well; and even amongst the people who know it

well, very few of those people know how to use it efficiently to the point

where grace and beauty can be seen in a simple spreadsheet!

This handout will take you from

the very beginning basics of Excel and then straight into a simple set of

efficiency rules that will lead you towards Excel excellence.

You use Word to create letters,

flyers, books and mail merges. You use PowerPoint to create visual, audio and

text presentations. You use Google to research a topic and find the local pizza

restaurant. You use Excel to make Calculations,

Analyze Data and Create Charts. Although databases (such

as Access) are the proper place to store data and create routine calculating

queries, many people around the planet earth use Excel to complete these tasks.

Excel’s row and column format and ready ability to store data and make

calculations make it easy to use when compared to a database program. However,

Excel’s essential beauty is that you can make calculations and analyze/manipulate

data quickly and easily “on the fly!” This easy to use, planet earth “default”

program must be learned if you want to succeed in today’s working world.

Open up The Excel Is Fun!.xls

workbook and click on the “What is Excel” sheet tab

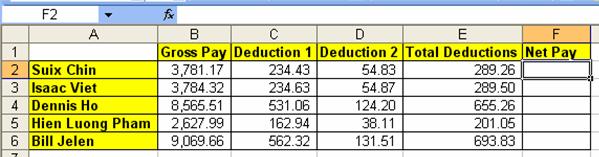

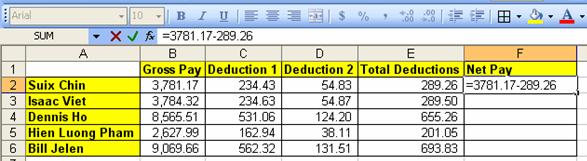

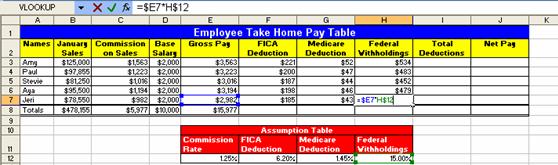

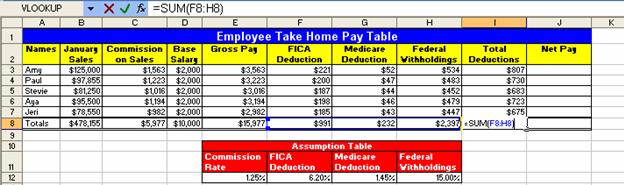

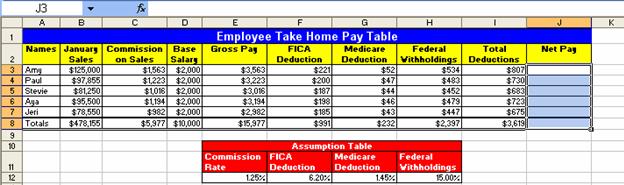

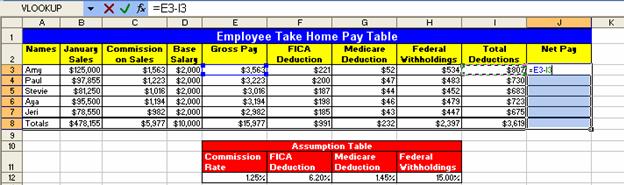

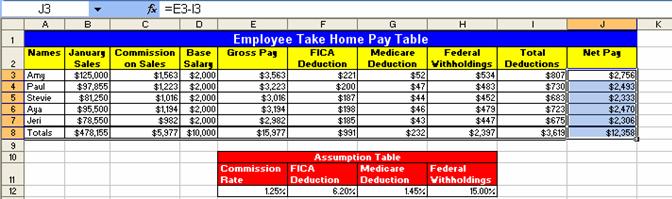

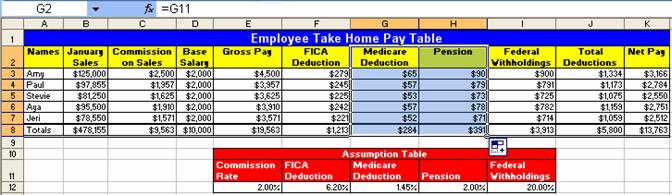

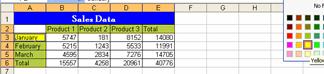

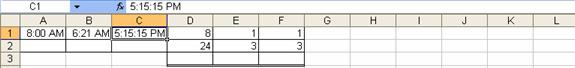

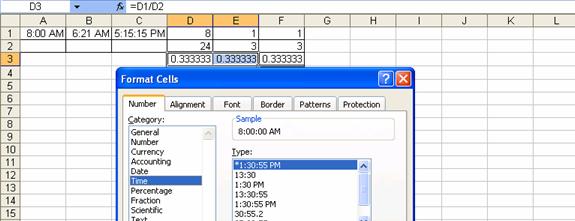

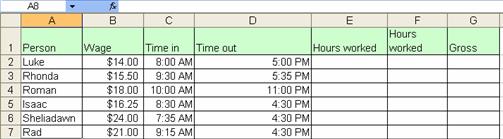

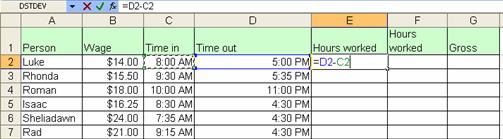

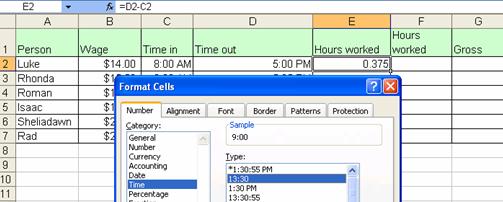

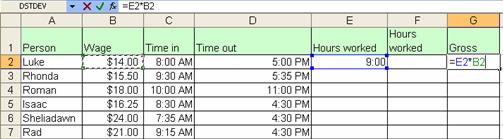

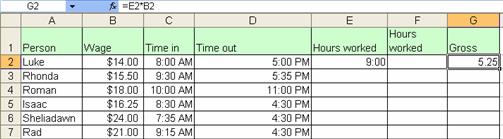

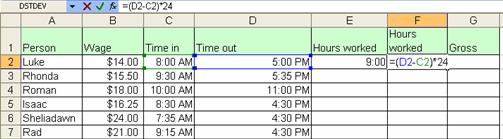

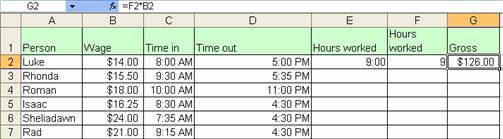

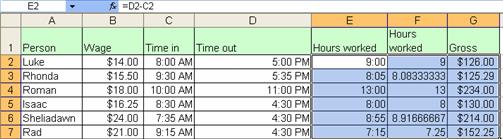

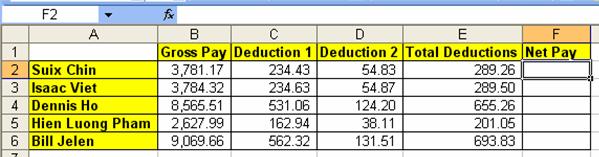

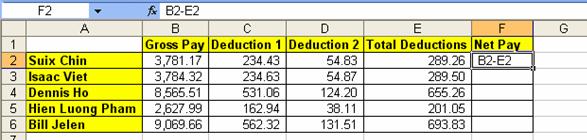

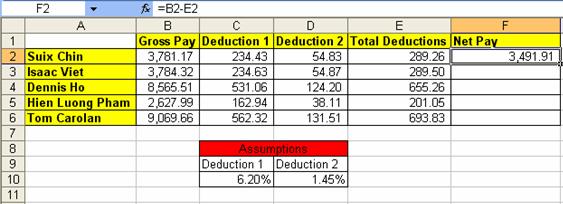

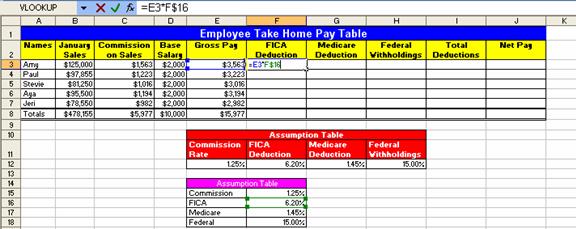

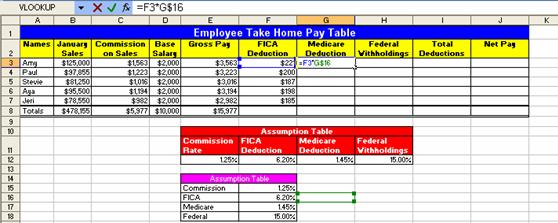

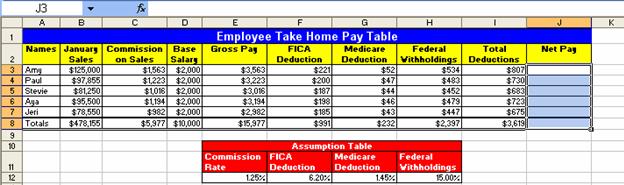

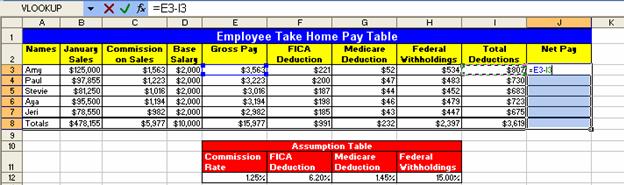

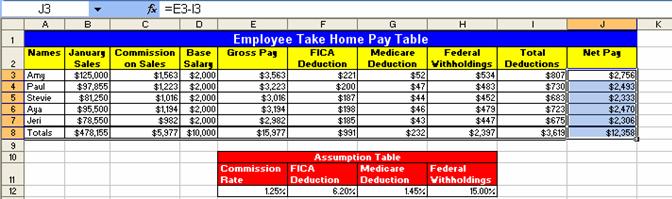

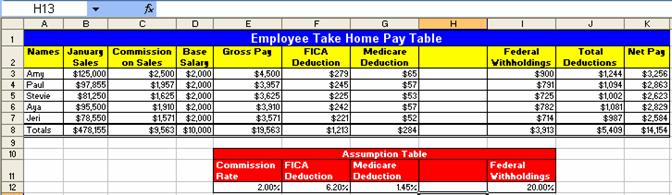

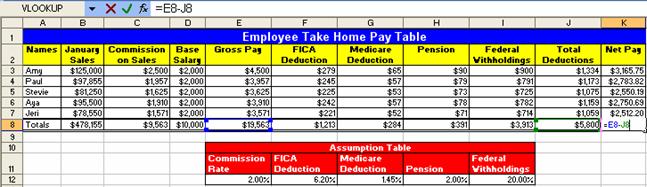

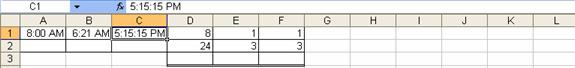

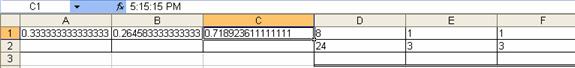

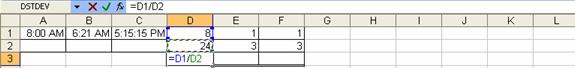

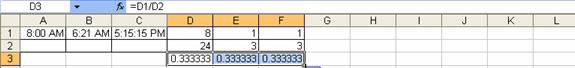

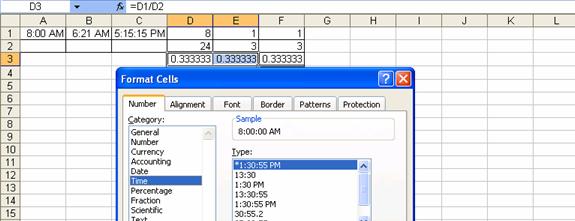

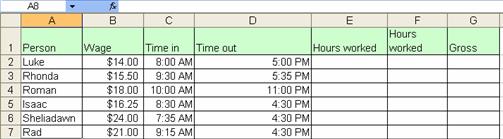

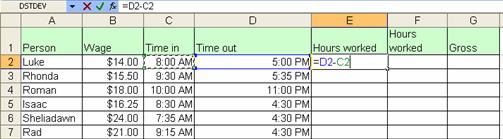

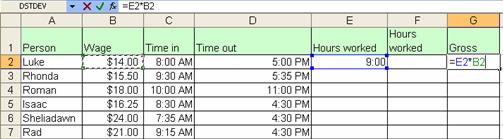

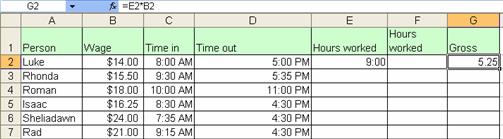

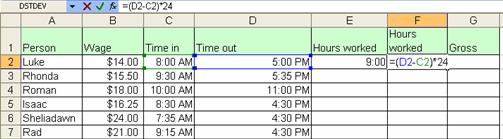

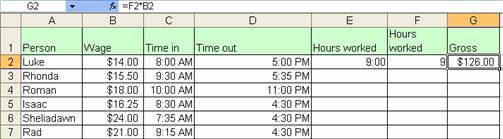

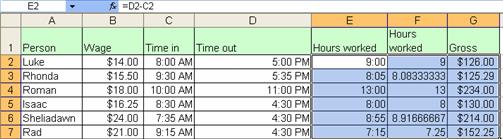

Here is an example of how Excel

can make payroll calculation quickly and with fewer errors than by hand (Figure

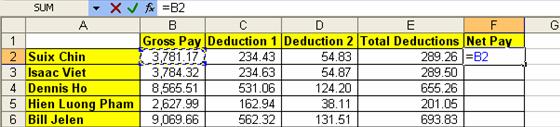

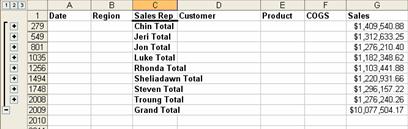

1):

Figure 1

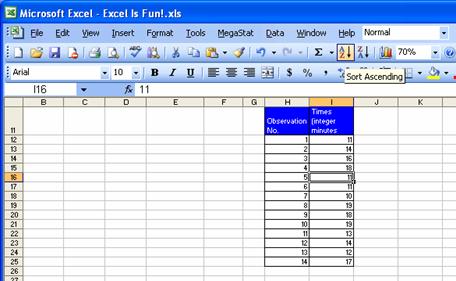

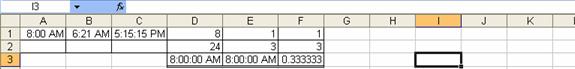

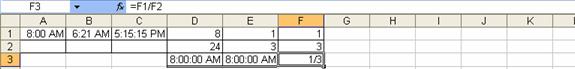

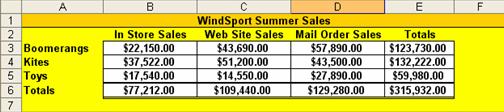

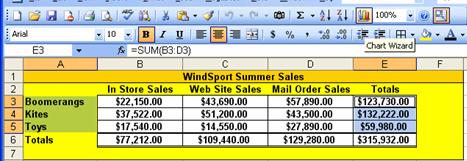

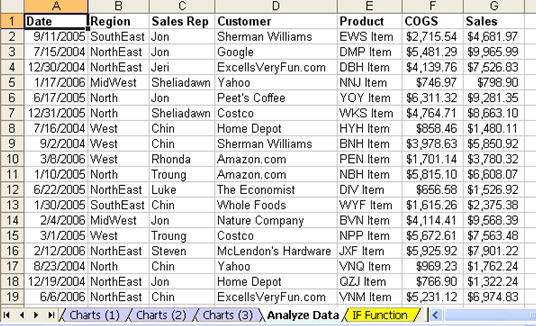

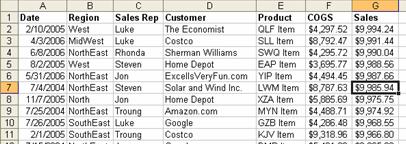

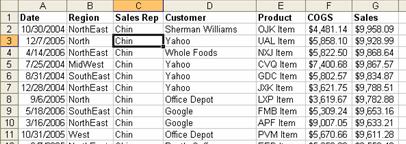

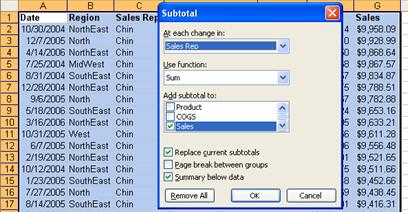

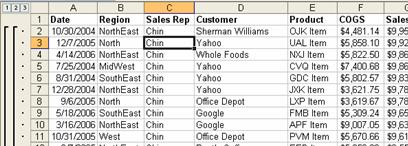

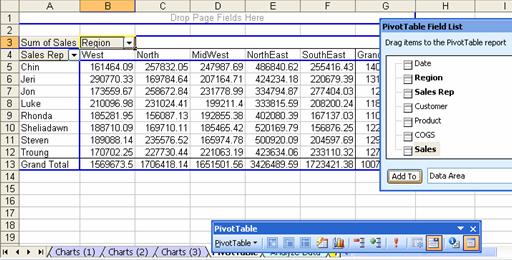

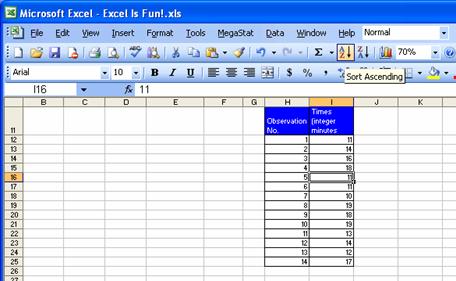

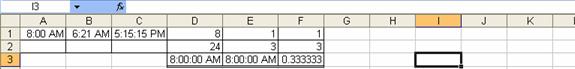

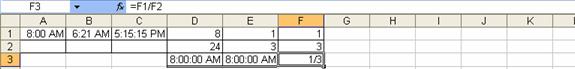

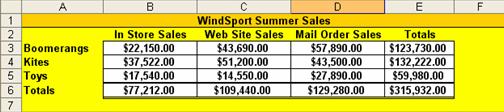

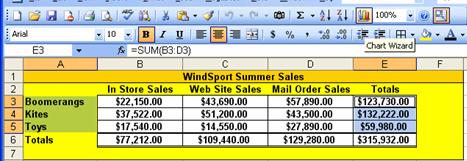

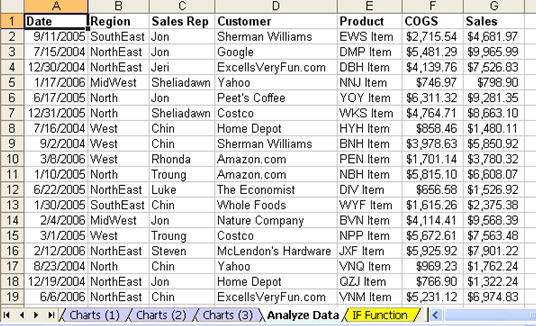

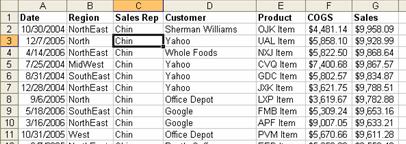

Here is an example of how Excel

can manage data, sorting by time, quickly and with fewer errors than by hand (Figure

2 and Figure 3):

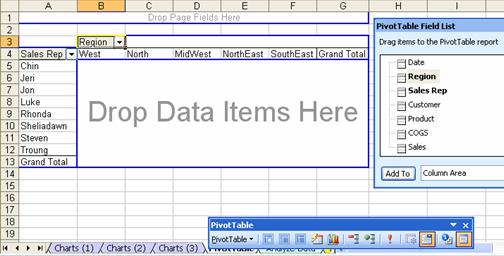

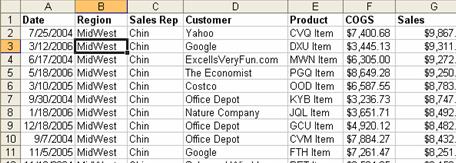

Figure 4

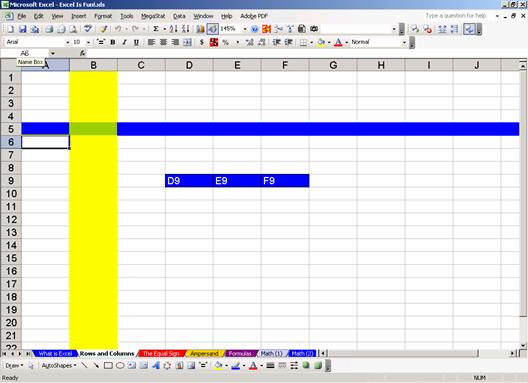

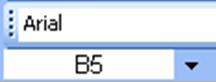

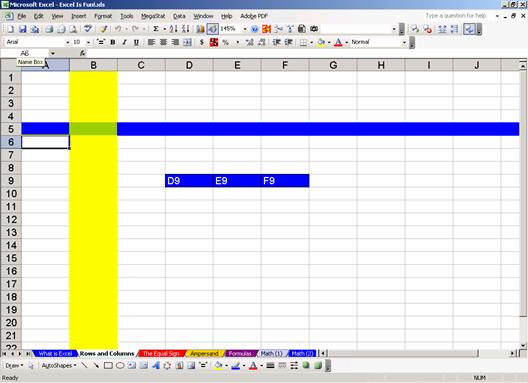

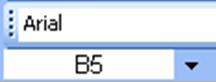

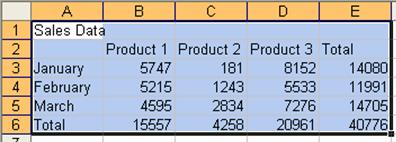

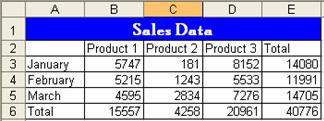

Rows are horizontal and are

represented by numbers. In our example (Figure 4)

the color blue has been added to show row 5.

Columns are vertical and

represented by letters. In our example (Figure 4)

the color yellow has been added to show Column B.

A cell is an intersection of a row

and a column. In our example the color green has been added to show cell B5. In

our example column B and row 5 can be detected because the column and row

headers are highlighted in a light-steel-blue color (Figure 4). In addition, you can see that the name box

shows that cell B5 is selected (Figure 4 and

Figure 5).

Figure 5

B5 is the name of this cell. It

can be thought of as the address for this cell. It is like the intersection of

two streets. If we wanted to hang out at the corner of Column B Street and Row 5 Street, we

would be hanging out at the cell address B5.

Later when we make calculations in Excel (making formulas),

B5 will be called a cell reference.

A range of cells is two or more

cells that are adjacent. For example you can see three blue cells D9, E9, and

F9. This range would properly be expressed as D9:F9, where the colon means from

cell D9 all the way to cell F9

Figure 6

A worksheet is all the cells

(65536 rows, 256 columns worth of cells). A worksheet is commonly referred to

as “sheet.”

The Sheet tab is the name of the

sheet. By default they are listed as Sheet1, Sheet2. In our example (Figure 6) the sheet we are viewing is named “Rows and

Columns.” You can see other worksheets that have been given names in our

example. Can you say what they are?

Naming your sheets helps you to

keep track of things in a methodical way. Navigating through a workbook,

understanding formulas and creating headers/footers is greatly enhanced when

you name sheets. To name your sheet, double-click the sheet tab (this highlights

the sheet tab name) and type a logical name that describes the purpose of the

sheet. Navigating through a workbook, understanding formulas and creating

headers/footers is greatly enhanced when you name sheets.

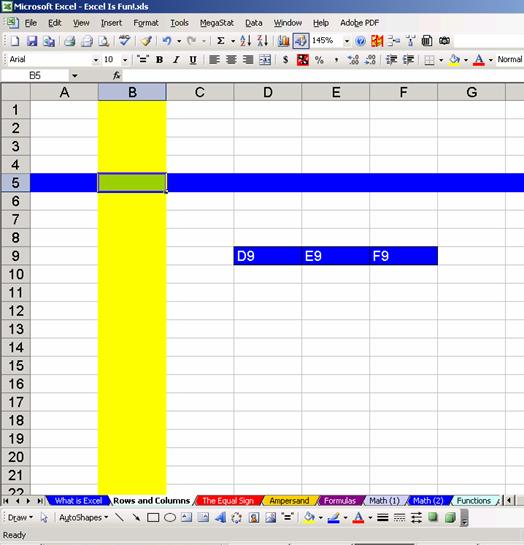

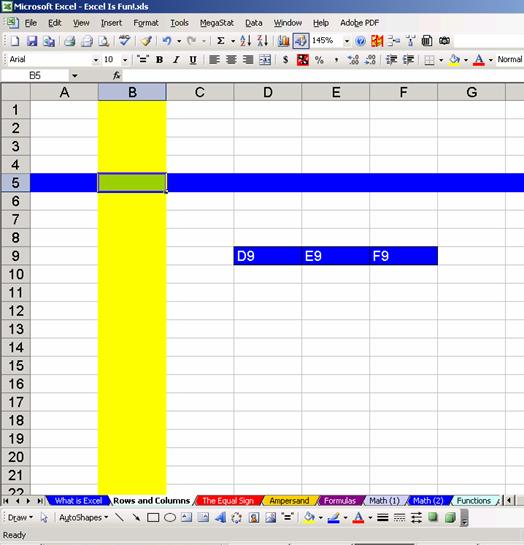

A workbook is all the sheets (up

to 256 worksheets). To name your workbook click the File menu and then Save As (Keyboard Shortcut = F12). Figure

7 shows the Save As dialog box:

Figure 7

Save in = Where do you want to

save it?

File name = what do you want to

call it?

Save as type = what type of file

is it? (.xls? or .htm? or .xlt?)

Naming your workbook helps you to

find it later and helps to create headers/footers.

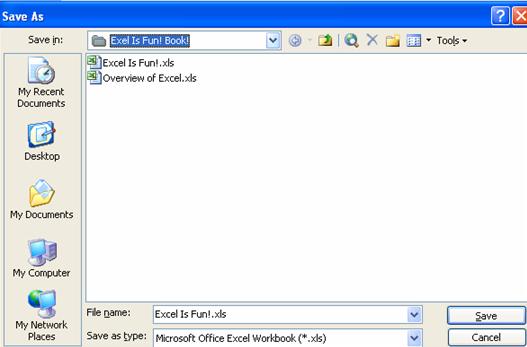

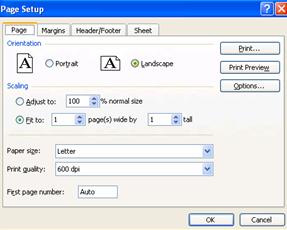

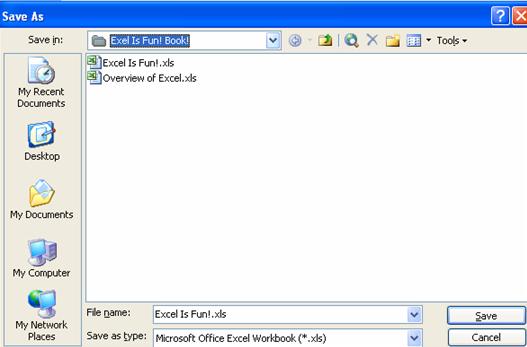

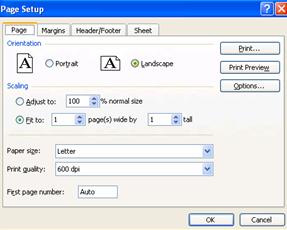

Menus allow you to access many of

Excel’s wonderful features. For example, if you want to change the page setup

from portrait to landscape, you could click the File menu and then click on

Page Setup as seen in Figure 8 Figure 9:

Figure

8 Figure

9

Notice that “File has an

underlined F and that Page Setup has an underlined u. Now

try to open up Page Setup with this keyboard shortcut: Hold down the Alt key,

then tap F once, then tap U once. The keyboard shortcut for opening Page Setup = Alt + F + U.

Also notice in Figure 8 Figure

9 that your menu may not have the MegaStat

menu. Don’t be alarmed. Not all menus are exactly the same. This is because you

can edit them and personalize them to suit your own needs.

Copy = Ctrl + C

Cut = Ctrl + X

Paste = Ctrl + V

Add bold to cell content = Ctrl + B

Add Underline to cell content = Ctrl + U

Add Italic to cell content = Ctrl + I

Select two cells and everything in-between = Click on first cell, hold

Shift, Click on last cell

Select cell ranges that are not next to each other = click on cell or range

of cells, Hold Ctrl, click on any number of other cells or range of cells

Ctrl + arrow key = move to end of range of data, or to beginning of next

range of data

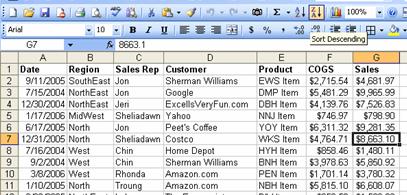

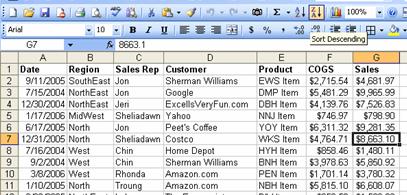

You can click on toolbar icons to

access many of Excel’s wonderful features. For example, you could highlight one

cell in the column of times and click the Sort Ascending button as seen in Figure

10 (notice when you hover your cursor

over a button, a screen tip pops up and names the button – in our case it says

“Sort Ascending”):

Figure 10

You could also click the Save,

Spelling and Undo buttons as seen in Figure 11:

Figure 11

However, instead of using these

three buttons learn your keyboard shortcuts: Save = Ctrl + S, Spelling = F7, Undo = Ctrl + Z.

Save and Undo are your best

friends. Save often so that when your computer crashes you don’t have to do

double work. Use undo when you accidentally do the wrong action. You can also

use Save and Undo in tandem: Click Save before you want to try a risky maneuver,

then try the risky maneuver up to 16 actions. Then click undo to go back to the

point where you saved (the down arrow next to Undo will allow you to highlight

a few undoes, click, and that will undo multiple actions).

Look at the toolbar in Figure 10, then go back and look at the toolbar in Figure

6. They are both different (these are

actual screen shots from my two different computers). Don’t be alarmed. All

toolbars are not the same. This is a good thing because it means that they are

customizable (a topic for a later time).

Save updates the already saved

file by replacing the stored file with the most recent changes.

Save As gives you the power to: 1)

Save the file to a new location 2) save file with a new name 3) change the file

type such as a template (.xlt), an earlier version of Excel (Microsoft Excel

5.0/95 Workbook (*.xls)), or a web page (*.htm;*.html). In this way the Save As

dialog box is very powerful.

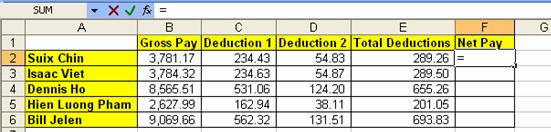

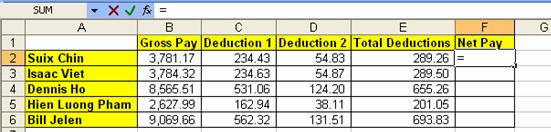

The equal sign, “=,” and the

join-operator (ampersand), “&,” are two magic symbols in Excel. We will

look at the equal sign first.

The equal sign tells Excel to create a formula in a cell. For

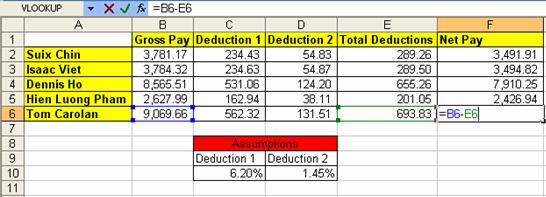

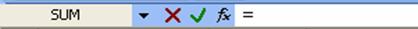

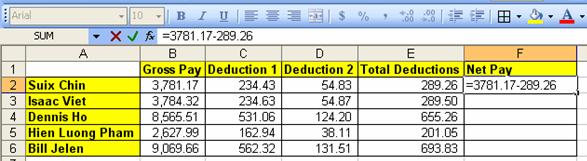

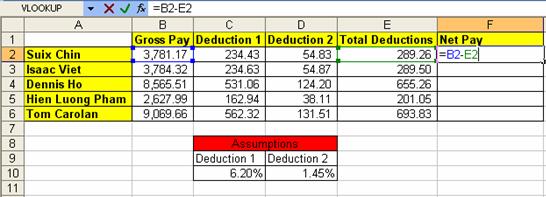

example, in Figure 12, if you would like

to calculate the net pay for Suix Chin in cell F2, what would you need to do?

You would need to take the net pay and subtract from it the total deductions.

In order to make this calculation in cell F2, you must first tell Excel that

you want to make a calculation by typing an equal sign: “=”.

Here are the steps to make

your first calculation in Excel:

1.

Using your “white, diagonally-pointing: cursor click on

the sheet tab named “The Equal Sign”. Next, using your “thick, white-cross” cursor

(it also has a black shadow) click in cell F2 in order to highlight the cell.

See Figure 12. Make sure that the name

box shows F2.

Figure 12

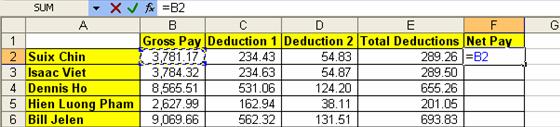

2. Type

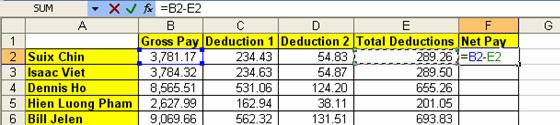

an equal sign. See Figure 13:

Figure 13

3. Notice

the equal sign in the formula bar as seen in Figure 14. (Don’t be alarmed that the name box has converted to an “Insert

Function” dropdown arrow – we’ll talk about this later).

Figure 14

4. Notes:

If you click the red x in Figure 14, you will cancel the formula in the middle of creating it

(Shortcut key = Esc)

If you click

the green check mark, The formula

is entered in the cell and the cell is selected (Shortcut key = hold Ctrl then

tap Enter)

The fx is a symbol from algebra that means “f of

x”, or function, or formula

5. Next,

using your “thick, white-cross” cursor, click in cell four to the left of F2

(cell B2). Like magic, Excel inserts the proper CELL REFERENCE after the equal

sign (see Figure 15). In addition, Excel

shines the blue and yellow flashlight around the cell B2 (these are the

colorful marching ants that march around the cell telling you that you have

placed the CELL REFERENCE B2 behind the equal sign).

Figure 15

6. The

formula is now looking at a cell that is four cells to the left of F2 – looking

at the cell named B2 which holds Suix Chin’s Gross Pay. Because our goal is to

calculate Net Pay, we still have to subtract the Total Deductions.

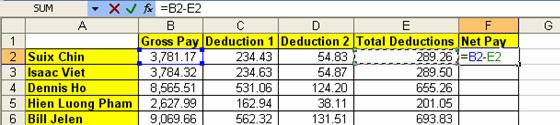

7. Type

a minus sign, then using your “thick, white-cross” cursor, click in cell E2,

which is one cell to the left of F2. You should see this (Figure 16):

Figure 16

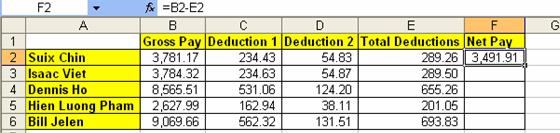

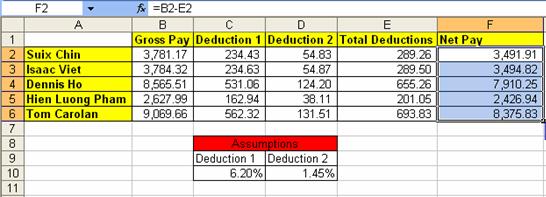

8. Hold

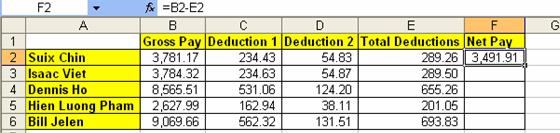

the Ctrl key, and then tap the Enter key once. This is what you should see (Figure

17):

Figure 17

9. You

have just created your first calculating formula in Excel by using the equal

sign as the first character in a cell. Although the cell F2 displays the take

home pay of 3,491.91, what is actually in the cell can be seen in the formula

bar. Our formula reads: please look at Suix Chin’s Gross Pay (four cells to the

left in B2) then subtract the Total Deductions (one cell to the left in E2).

10. We have

creating our first calculation in Excel, and what we actually created is called

a formula. Because the equal sign is the first character in the cell we told

Excel to create a formula. If there was no equal sign, there would be no

formula. In addition, we used CELL REFERENCES. CELL REFERENCES are our way of

telling our formula to look into a different cell and use that value in our

formula!

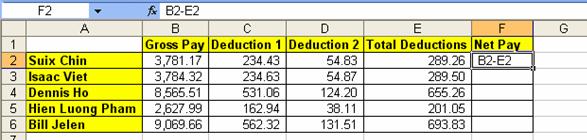

11. What would

have happened if you did not place an equal sign in the cell as the first

character but you still typed the rest of the formula (Figure 18)? Excel would obey you and not create a

formula, but instead place the typed text “B2-E2” in the cell.

Figure 18

12. What would

happen if you type the number for gross pay and the number for total deductions

in the formula instead of the cell references? Here is an example of this

situation, however, please burn this image into you brain as something you

should NEVER do (Figure 19):

Figure 19

13. Excel will

obey you and calculate an answer. However, if you want to become even moderately

efficient with using Excel, NEVER TYPE NUMBERS THAT CAN VARY INTO A FORMULA.

When you enter numbers that can change (or text) into formulas instead of

references to other cells:

i.

Editing the formulas later on can become nearly

impossible

ii.

What-if or scenario analysis becomes cumbersome

iii.

The true magic of Excel is greatly dimmed, as if a

magnificent rainbow that fills the sky with refreshing color is suddenly all

one color of grey.

14. Numbers

such as the number 12 that represents months is OK to type into a formula.

Similar numbers would be things like 7 days in a week, 24 hours in a day.

The second magic symbol in Excel is the Ampersand (more

commonly known as the “and” symbol) “&”. This symbol joins the content from

two or more cells, results from formulas, or text, and places them all into one

cell. To see an example, click on the sheet tab named “Ampersand”.

Here are the steps to join

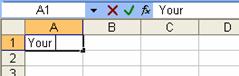

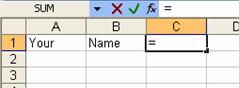

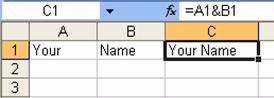

the words “Your” and “Name” and place them into one cell.

1. In

cell A1 type “Y o u r” (letters Y, o, u, r, space). You should see this (Figure

20):

Figure 20

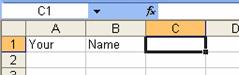

2. Hit

Tab. In cell B1 type “N a m e” (letters N , a, m, e), and then Tab. You should

see (Figure 21):

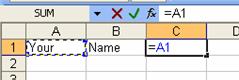

Figure 21

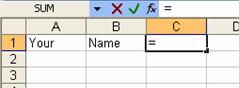

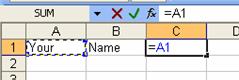

3. In

cell C1 type the an equal sign (Figure 22):

Figure 22

4. Hit

the left arrow key twice (Figure 23):

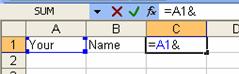

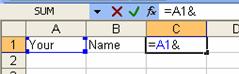

Figure 23

5.

Type the

Ampersand (Shift + 7) (Figure 24):

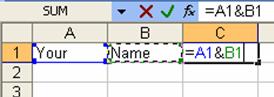

Figure 24

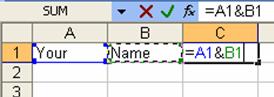

6. Hit

the left arrow key once (Figure 25):

Figure 25

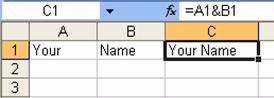

7. Hit

Ctrl + Enter (Figure 26):

Figure 26

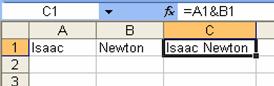

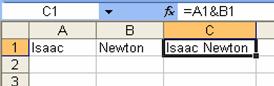

8. In

cell A1 type “Isaac ” and in cell B1

type “Newton” (Figure

27):

Figure 27

9. Now

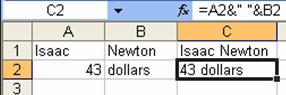

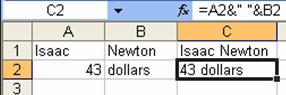

try your own joining using the “&” (Figure 28):

Figure 28

Method of placing cell references in formula after you have placed an equal

sign as the first character in the cell: 1) use mouse to click on cell, 2) use

arrow keys to move to cell reference location, 3) type the cell reference

(higher probability of error)

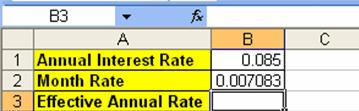

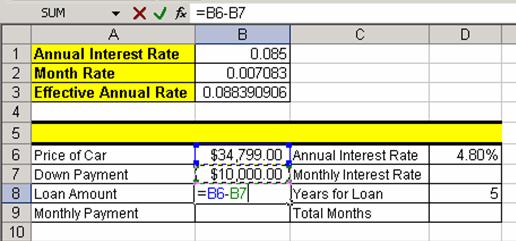

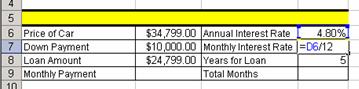

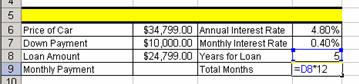

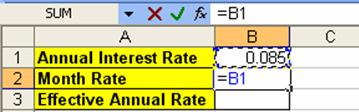

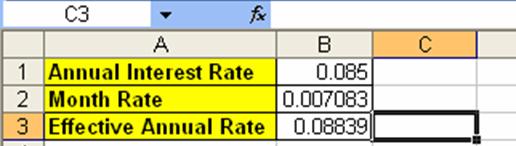

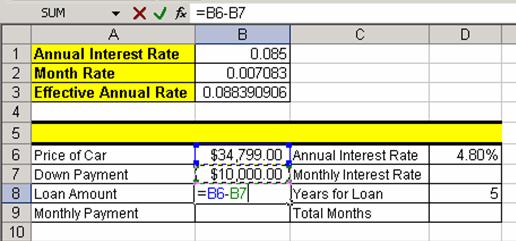

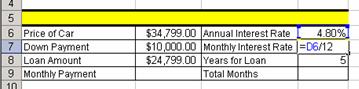

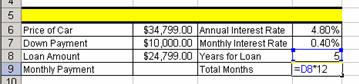

Here are the steps to

calculate a monthly interest rate on a loan

1. In

your “Excel Is Fun!.xls” Workbook, click on the sheet tab named “Formulas”

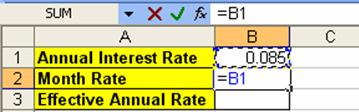

2. As

seen in Figure 29, click in cell B2 and

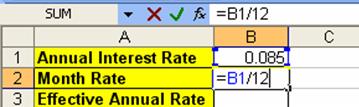

type an equal sign. By typing the equal sign, you are telling Excel that you

are creating a formula in cell B2.

Figure 29

3. Click

the up arrow key (in between the letter keys and the number keys). By typing

the up arrow, you are telling Excel that you would like the formula to look

into the cell “one above” B2 and get the annual rate of .085. You should see

what is in Figure 30:

Figure 30

4. Notice

that by using the arrow key to select a cell reference, you save the time it

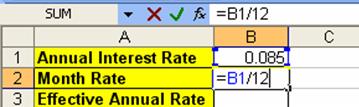

would take you to grab the mouse and click on cell B1.

5. Type

the division symbol “/” and the number 12 (12 months in a year does not vary so

that fact that this is a number does not violate Rule #6). See Figure 31:

Figure 31

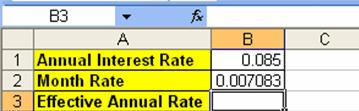

6. Tap

Enter. Taping the Enter key puts the formula in the cell and moves the cursor

one cell below B2 to the cell B3. The monthly rate displayed in the cell can be

seen in Figure 32:

Figure 32

So far we have seen two keystrokes that tell Excel that the

formula is completed and we would like to have Excel show us the result. The

keystrokes “Ctrl + Enter” and “Enter” will officially enter the formula into

the cell. The “Tab” key will do this also. These three keys are the safest

keystrokes for putting the formula into the cell. There are other keystrokes

that work some of the time, but not all the time. For safety and efficient

formula creation we will only use Ctrl + Enter, Enter, or Tab to enter formulas

into cells. If we use only these three keystrokes to place formulas in cells we

can avoid unintended cell reference insertion that can cause our formula to be

inaccurate.

To enter a formula into a cell use “Ctrl + Enter” to place

the formula in the cell and select the cell, use Enter to place the formula in

the cell and select the cell directly below the cell with the formula, or use

Tab to place the formula in the cell and select the cell one to the right

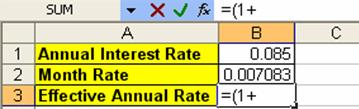

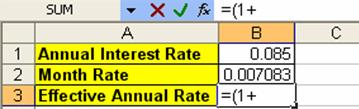

7. In

Cell B3, type: “=(1+”, as seen in Figure 33:

Figure 33

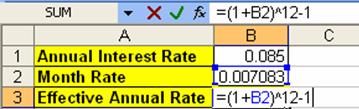

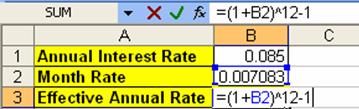

8. Click

the up arrow once, then type: “)^12-1”

as seen in Figure 34 ( ^ symbol = Shift +

6):

Figure 34

9. We

do not violate rule # 6 (DO NOT TYPE DATA THAT CAN VARY INTO A FORMULA) by

typing the 1, 12, and 1 into these formulas. For calculating the annual

effective rate from a month rate these numbers do not vary!

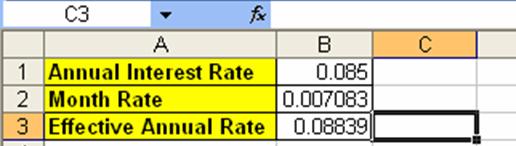

10. Click Tab.

You should see this (Figure 35):

Figure 35

11. But what is

that “^” symbol mean???

Figure 36

As seen in Figure 36, we will have to learn the Arithmetic

operation signs in Excel. In addition, we will have to learn the order of

operations in order to avoid analysis mistakes. For example, what is the answer

to 3 + 3 * 2? Is it 12 or is it 9? Because Excel knows the order of operations,

we must also know the order of operations so we can calculate correctly. For a

refresher in the order of operations, read Figure 36.

Here are the steps to practice

math and the order of operations:

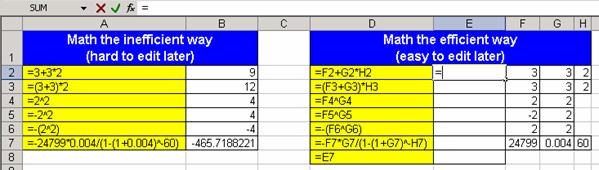

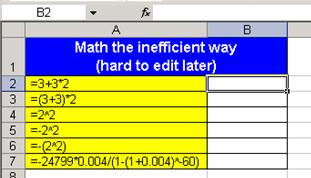

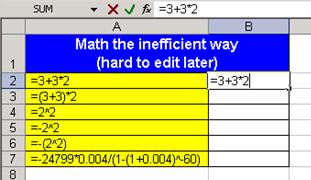

1. Click

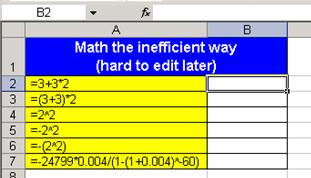

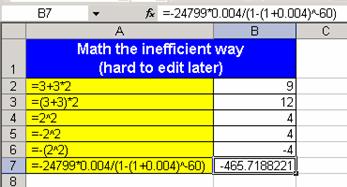

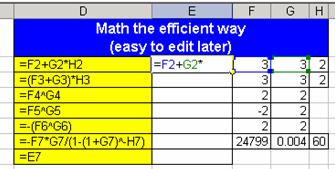

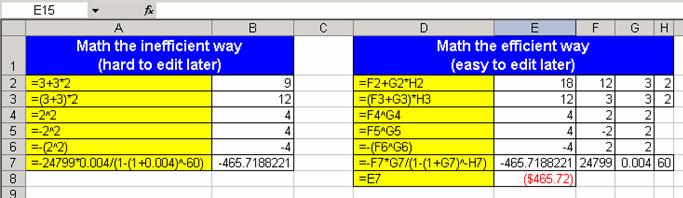

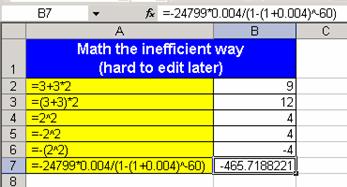

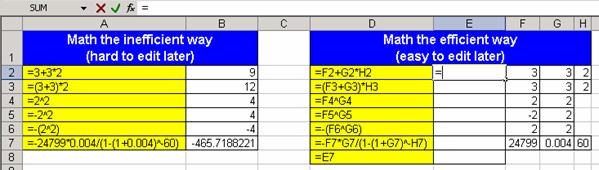

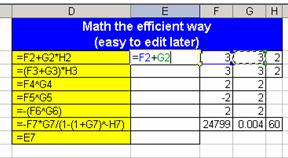

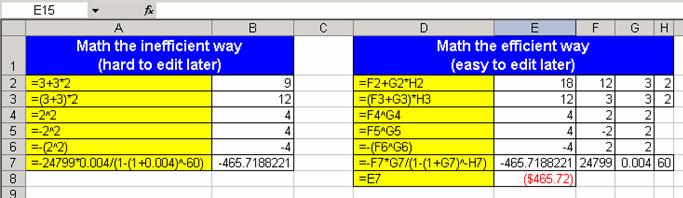

on the sheet tab named “Math (2)”. You should see this (Figure 37):

Figure 37

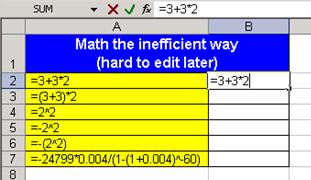

2. Click

in cell B2 and type the formula “=3+3*2”. You should see this (Figure 38):

Figure 38

3. Looking

at the examples of formulas in column A, create the remaining formulas in

column B. When you are done you should have these results (Figure 39):

Figure 39

4. The

problem with what you just did (Figure 37,

Figure 38, Figure 39), is that editing the formulas later is inefficient when

compared to a method that employs cell references. Our next example will employ

cell references.

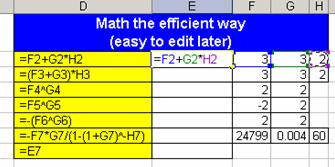

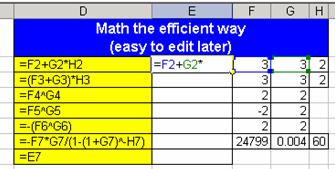

5.

Click in cell E2 and type an equal sign “=” (Figure 40).

Figure 40

6.

Click the right arrow key, as seen in Figure 41:

Figure 41

7.

Type “+”, as

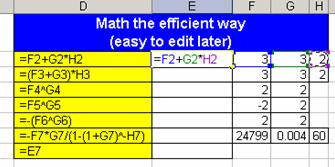

seen in Figure 42:

Figure 42

8.

Click the right arrow key twice, as seen in Figure 43:

Figure 43

9.

Type the “*”, as seen in Figure 44:

Figure 44

10. Click

the right arrow three times, (Figure 45):

Figure 45

11. Hit

Enter. The answer should be 9.

12. In

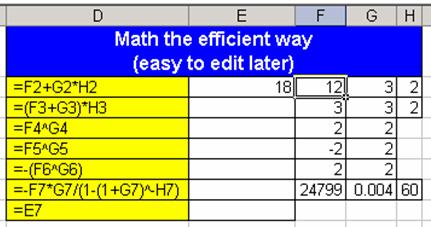

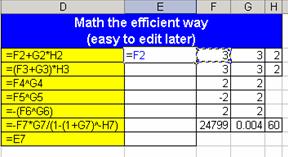

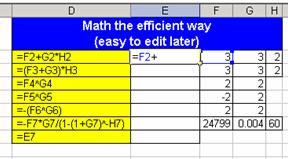

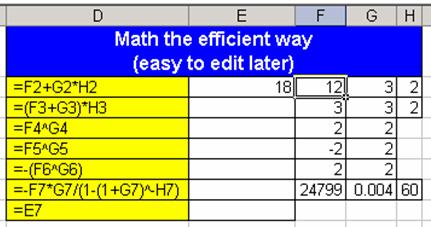

Figure 46 the heading says “Math the

efficient way”. The efficiency comes from the fact that it is easy to edit

these formulas because you have utilized cell reference that point to numbers

typed into cells. Change the number in cell F3 to 12 and watch your formula

change (Figure 46):

Figure 46

13. Look

at the formulas in column D) and create the corresponding formulas in column E.

When you are done you should see this (Figure 47):

Figure 47

14. But

what is going on in cell E8? How come when cell E8 looks at cell E7 it shows us

a dollar figure? The answer comes from formatting. We will talk about

formatting later (this is exciting foreshadowing)…. For the time being we have

been taking about the equal sign, ampersand sign, numbers, cell references and

math operators: these are all components of formulas. We will now formally

define a formula in Excel è.

Definition of a

formula: Anything in a cell when the first character is an equal sign.

(Anything in a cell or formula textbox when the first character is an equal

sign and the cell is not preformatted as Text).

Advantages of a

formula: You are telling Excel to do calculations, look into another cell,

create text strings, or deliver a range

How to create a formula: Type “=,” followed by:

1. Cell

references (also: names and sheet references)

2. Operation

signs

3. Functions

4. Text

that is in quotes (ex: “For The Month Ended”)

5. Ampersand

symbol: &

i.

To combine information from different cells, text in

quotes, or functions use the ampersand: &

1. Example:

="For The Month Ended "&B5

ii.

To Extend the upper limit for Functions

1. Example:

Extend IF upper limit of seven to more than seven

6. Numbers

i.

The only numbers that ever go in a formula are numbers

that will never change (such as the number of months in a year)

How to enter a formula into a cell: hit one of the following:

7. ENTER

8. Ctrl

+ Enter

9.

Tab

Here are the steps to

create five formulas:

1.

You are currently looking at the sheet tab named “Math

(2)”. Make sure that you are in this sheet

2.

Hold down Ctrl, then tap the “Page Up” key twice

(Ctrl + Page Up è

moves you up through the sheets)

(Ctrl + Page Down

moves you down through the sheets)

3.

You should now be located in the sheet tab named

“Formulas”

4.

Create the following formula (as seen in Figure 48). Efficient key strokes are: “=”, up arrow

twice, “-“, up arrow once.

Figure 48

5.

Hit Tab twice, Arrow up and create this formula in D7 (Figure

49):

Figure 49

6.

The 12 represents months in a year and does not change

and so it is efficient to type this number into a formula

7.

Hit Enter twice and create this formula in D9 (Figure 50):

Figure 50

8.

Click in cell B9 and create the formula as seen in Figure

51. After you create it, hold Ctrl, and

then tap Enter.

Figure 51

9.Click in cell A5. The cell is merged

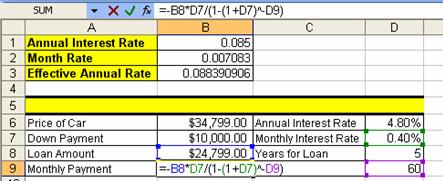

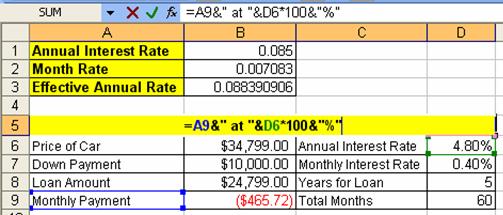

and centered and so the formula will be created in the middle of the range. Create

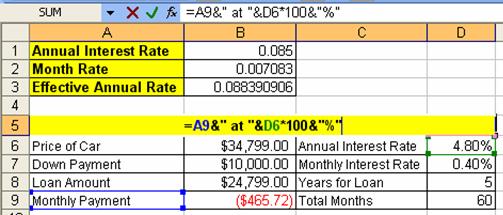

the following formula as seen in Figure 52:

Figure 52

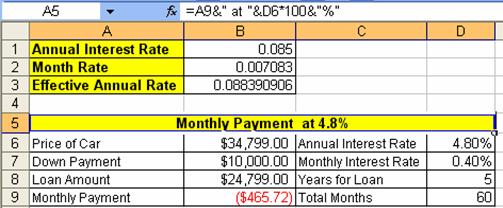

10. This

formula combines cell references, text in quotes and a calculation all joined together

with the Ampersand “&”. The resulting label for our calculations can be

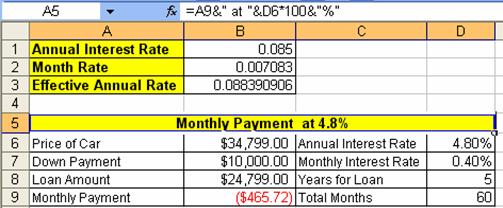

seen in Figure 53:

Figure 53

11. The

efficiency and beauty of building a spreadsheet in this manner is revealed when

we change the source data and then watch our formulas change automatically.

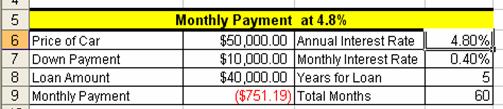

12. Click in cell B6 and change the price of the car to

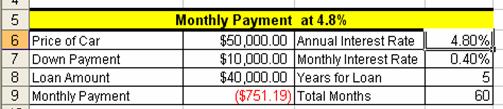

50,000 (type 50000), then hit Tab twice. (Figure 54):

Figure 54

13. Notice

that the preformatted cells formatted the “50000” to appear as

“$50,000.00”. Also notice that our formulas for Loan Amount and Monthly Payment

updated.

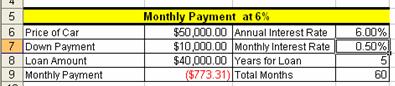

14. Verify

that you are in cell D6 and then type “6” and then hit Enter (Figure 55):

Figure 55

15. Notice

that the three formulas that were dependent on the Annual Interest Rate all

updated when we changed the rate. This ability to check different scenarios

without much effort is at the heart of using Excel efficiently. We always want

to strive to build our spreadsheets efficiently so that they are easily edit-customizable

at any time! By typing the numbers that can vary into cells and referring to

them using cell references in our formulas we have accomplished Excel

efficiency and fun!

16. Look in the lower left corner of Figure 56 and find the scroll arrow for sheet tabs.

The little black triangle turned on its side means show me one more sheet tab.

The little black triangle turned on its side with an extra vertical line means

take me all the way to the last and/or first sheet tab.

Scroll arrow that reveals more sheet tabs

|

|

Figure 56

17. Click

the sheet tab scroll arrow twice as seen in Figure 57:

Figure 57

18. You

should see a few more sheet tabs exposed. The sheet tab “Formulas” is still

selected, however, by clicking the sheet tab scroll arrow more sheets are

exposed (Figure 58):

Figure 58

19. Move

to the sheet tab named “Functions” by either clicking on the sheet tab named

“Functions”, or by Holding Ctrl, then tapping the “Page Down” key three times.

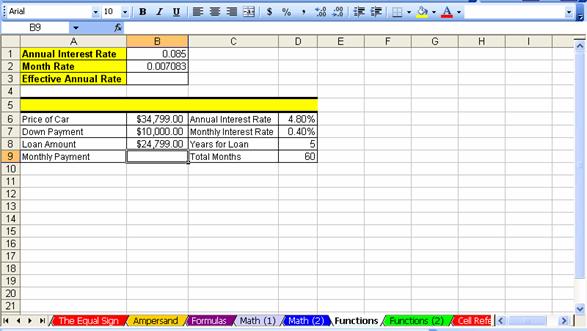

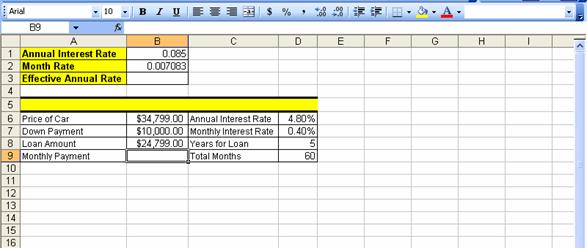

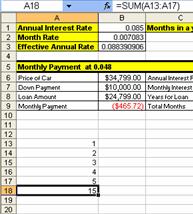

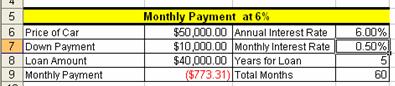

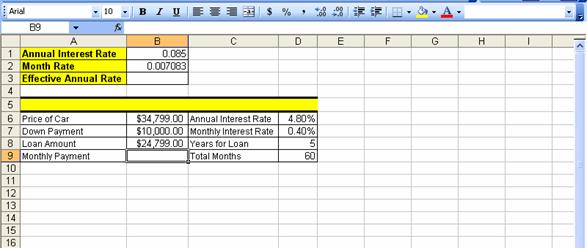

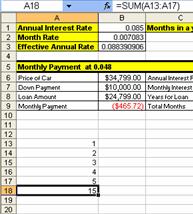

You should see this (Figure 59):

Figure 59

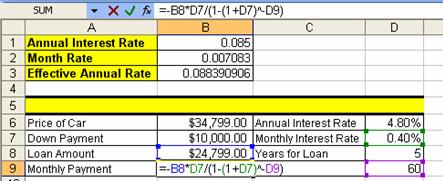

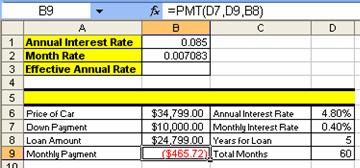

20. Click

in cell B9. What if we want to calculate the monthly payment for our car loan,

but we do not know that math formula? Luckily there are built in “FUNCTIONS”

that know how to do this – as long as we can tell the FUNCTION what the monthly

rate, number of months and present value of our loan is, the function will do

the rest!

What are functions? Built in code that

will do complicated math (and other tasks) for you after you tell it which

cells to look in

Examples:

SUM function

(adds)

AVERAGE function

(arithmetic mean)

PMT function

(calculate loan payment)

COUNT

function (counts numeric values)

COUNTA

function (counts non-blank cells)

COUNTIF

function (counts based on a condition)

ROUND

function (round a number to a specified digit)

IF function (Puts one of two items

into cell depending on whether the condition evaluates to true or false)

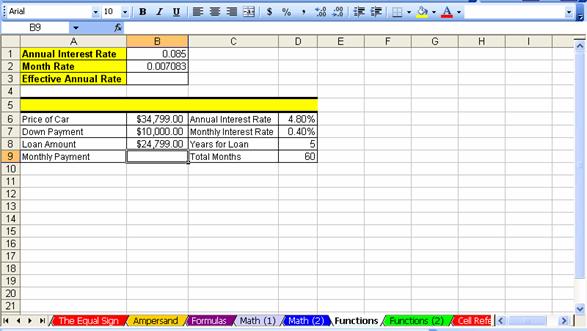

Here the steps to practice

with many new Functions:

1.

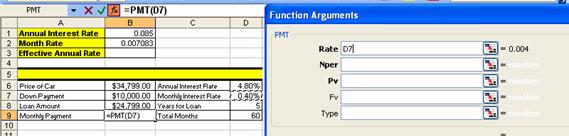

Click in cell B9 and then click the fx

button (Insert function button) in the formula bar (Figure 60). (Keyboard shortcut: Shift + F3 = Open Insert Function dialog box)

fx button è the

insert function button

|

|

Figure 60

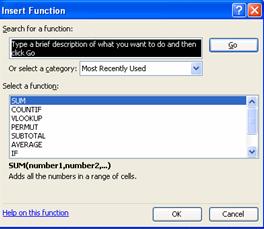

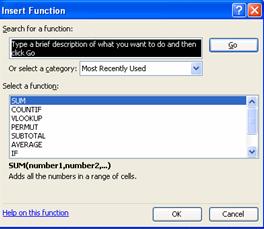

2.

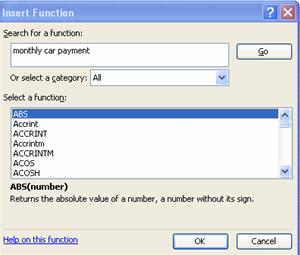

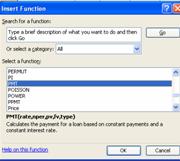

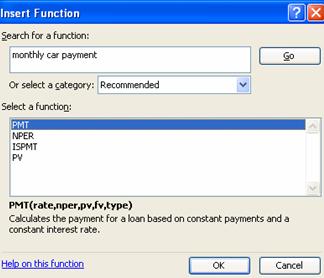

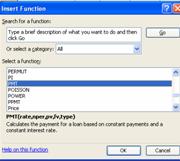

The Insert Function dialog box looks like this (Figure 61):

Figure 61

1.

There are five key parts to the Insert Function dialog

box:

1.

Search

2.

Category

3.

Select function

4.

Description of selected function

5.

Help

2.

Click in the search for a function text box and type

“monthly car payment” then hit Enter (Figure

62):

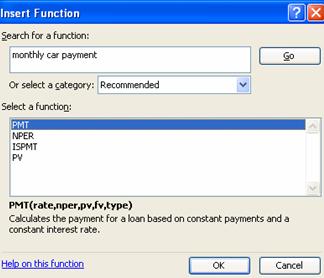

Figure 62

3.

In the select a function list the first function

selected is “PMT”

4.

Below the list is the description: “Calculates the

payment for a loan based on constant payments and a constant interest rate.” This

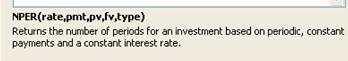

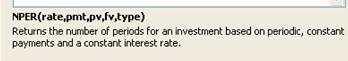

sounds perfect for our need. But let’s check the others to make sure that there

is not something even better. Click on “NPER.” Figure 63 shows the description

of this function:

Figure 63

5. After

looking at each function, click back on the PMT function because, amongst the

four options, it fulfills our goal most satisfactorily. Descriptions are the

key to the Insert Function dialog box. You can find the most amazing functions

that will do all the calculating for you if you just spend a little time “hunting”

(looking through the list of functions).

6.

Because “hunting for the right function is the key to

learning about all the wonderful built-in functions, another way is to “hunt”

using the “All” category.

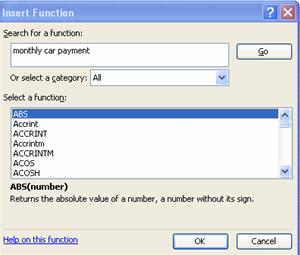

7.

Click the down-arrow next to “Select a category” and

point to All (Figure 64):

Figure 64

8.

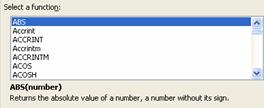

Most of the functions have common sense names. See if

you can find a function that will calculate “Absolute value”, “Geometric mean”,

“Average”, “Straight-line depreciation”. All four of these can be found by

hunting for those words in the list.

9.

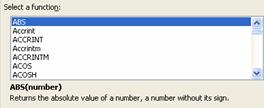

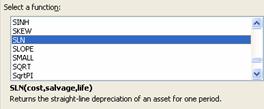

Absolute value (Figure 65):

Figure 65

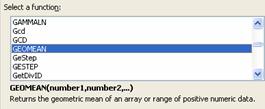

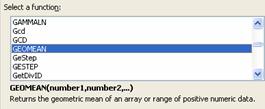

10. Geometric

mean (Figure 66):

Figure 66

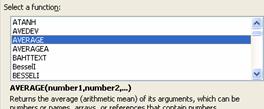

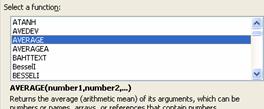

11. Average

(Figure 67):

Figure 67

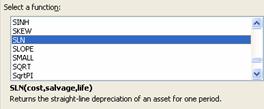

12. Straight-line

depreciation (Figure 68):

Figure 68

13. Now, find

the PMT function again. (Figure 69):

Figure 69

14. Double

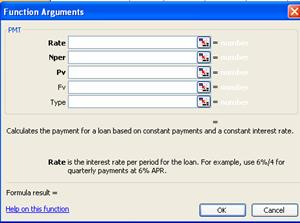

click the highlighted PMT function to open the Functions Arguments dialog box (Figure

70):

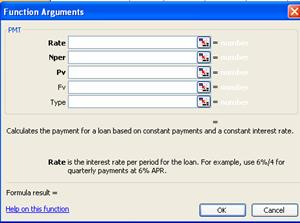

Figure 70

15. The

arguments “Rate” “Nper” and “Pv” are in bold and the most commonly used variables for this

function and are required for the function to give you a result. The “Fv” and

the “Type” are not in bold and are not required. There is a description for

each argument that will help you figure out how to use the function. In

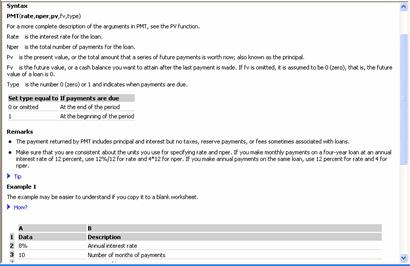

addition, “Help on this function” (bottom lower left corner of Figure 70) is amazing! If you click that link it will give

you a full description and example of how to use this function. The help looks

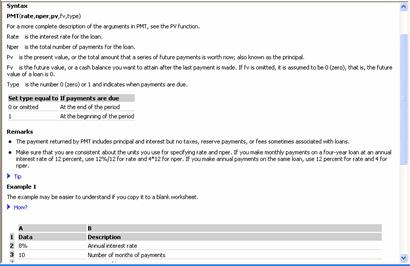

like this (Figure 71):

Figure 71

16. If you

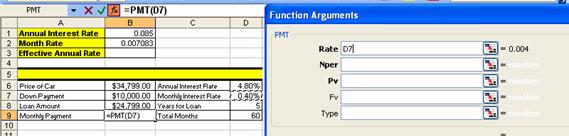

opened up the help, close it. Make sure your curser is in the argument box for Rate, then click in cell D7 (Figure 72):

Figure 72

17. Notice that

when you click on cell D7 the value is shown to the right side of the argument

box.

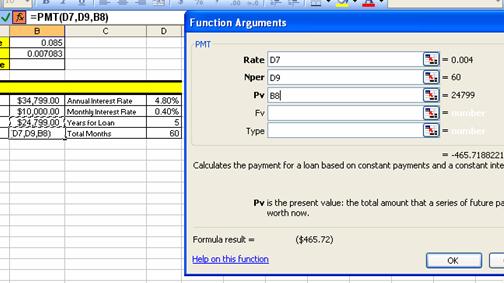

18. Hit Tab to

move to the next argument box, click in cell D9, Hit Tab, Click in cell B8 (Figure

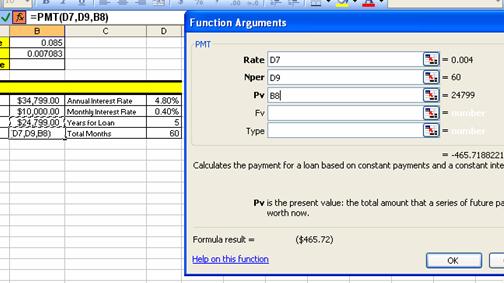

73):

Figure 73

19. In Figure

73 notice:

1. Each

argument box has a cell reference (this makes it easy to edit later)

2. To

the right of each argument box that the variable amount is shown

3. The

formula result is shown in two different locations (can you see both?)

4. The

formula bar shows that Excel has placed an equal sign in the cell for you, that

the name of the function is in the formula and that the three cell references

(arguments) are separated with commas.

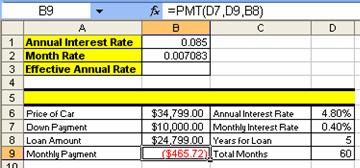

20. Click OK.

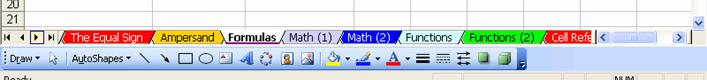

The result is the same as when we made our calculations before without the use

of an Excel function. (Figure 74):

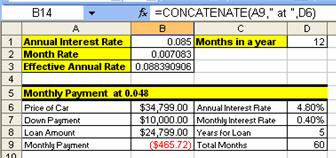

Figure 74

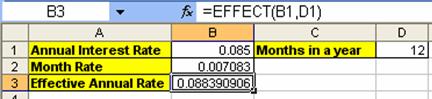

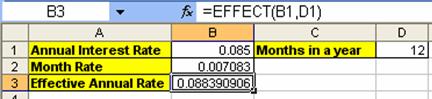

21. Click in

cell B3 and use the Insert Function dialog box to find a formula for

calculating the Effective Annual Rate. The result should look like this (Figure

75):

Figure 75

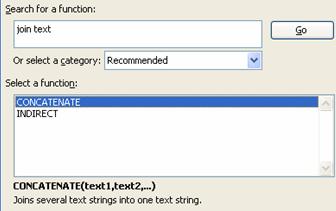

22. Click in

cell A5 and then hold the Shift key and tap the F3 key. In the Search for a

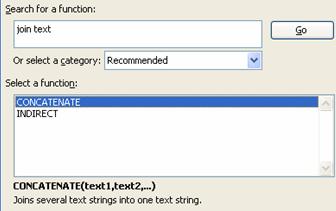

function text box type “join text” (Figure 76):

Figure 76

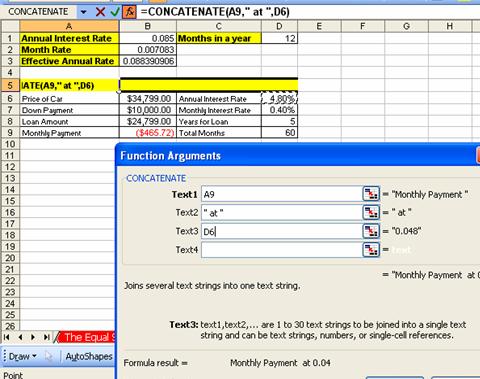

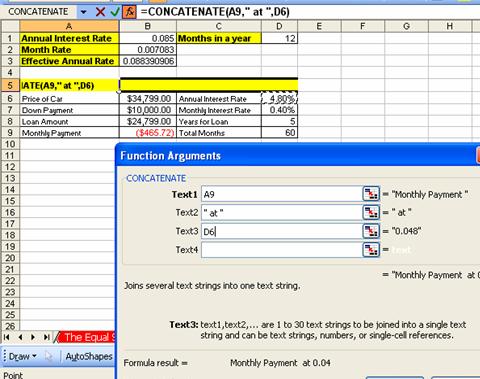

23. Create the

label for the Monthly Payment table (be sure to pay attention to the spaces

before and after the word “ at “) using the Concatenation function (Figure 77):

Figure 77

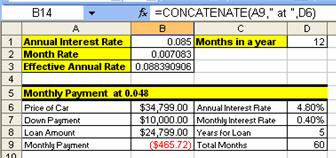

24. The result

looks like this (Figure 78):

Figure 78

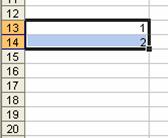

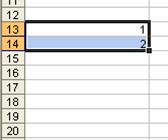

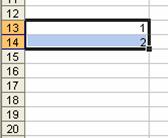

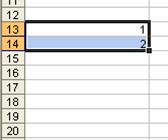

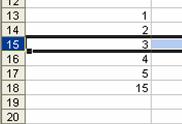

25. Type the

number “1”

into cell A13 and the number “2”

into cell A14. Then highlight the two cells (Figure 79):

Figure 79

26. Look at Figure

79. What is that little black box in the

lower right corner of the highlighted range? It is called the fill handle. It

is magic. Take your cursor and point to it until you see a cross hair (angry

rabbit). (Figure 80):

Figure 80

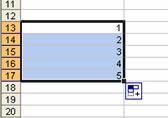

27. Click and

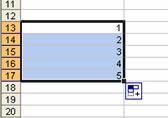

drag the angry rabbit down to A17. Just like magic Excel assumes you want to

add by 1 because the pattern of the number 1 and 2 is to always add 1. (Figure 81):

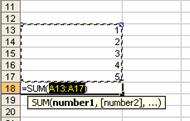

Figure 81

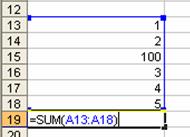

28. Click

in Cell A18. We are going to add all the numbers by using a SUM function. The keyboard shortcut for the SUM function is Alt +

“=”.

29. Hold the Alt key, then tap “=” (Figure

82):

Figure 82

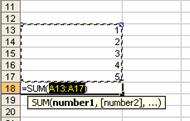

30. In Figure 82 we see that the SUM function tries to guess

what data we want to sum (it does not always guess correctly). It guessed

correctly this time and so we hit Ctrl + Enter (or if we are still holding the

Alt key we would tap “=” a second time. (Figure 83):

Figure 83

31. It is much more

efficient to use the SUM function, “=SUM(A13:A17)”, than it is to type in “=A13+A14+A15+A16+A17”.

In addition there is an added bonus to using a function that uses a range such

as A13:A17. Let’s take a look è

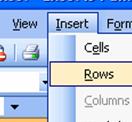

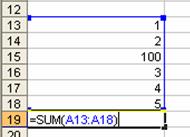

32. Point to

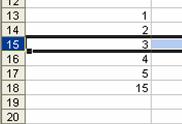

the row heading 15 and click to highlight the whole row (Figure 84):

Figure 84

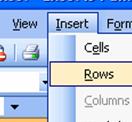

33. With the

row highlighted click on the Insert menu and point to Row without clicking (Figure

85):

Figure 85

34. Notice the I

and R.

35. Click Esc

36. Make sure

that Row 15 is highlighted and then hold the Alt key and tab I, and then

tap R. The result is that you have inserted a row (Figure 86):

Figure 86

Keyboard shortcut Insert Row = Alt + I + R

37. Click in

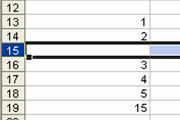

cell A15 and type the number “100”

and hit enter (Figure 87):

Figure 87

38. Notice that

the sum function updated

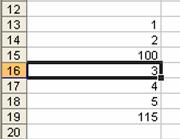

39. Click in

cell A19 and click the F2 key (Figure 88).

Keyboard shortcut for Range Finder = F2

Figure 88

40. Range

Finder allows us to audit a formula after it is created. Look at the range we

have in Figure 88 (A13:A18). Now look at

the range in Figure 83. Our conclusion:

by using a function with a range our formula will update when we insert rows or

columns.

41. For more

practice with Functions go to the sheet tab named “Functions (2)”

42. Hover your

“thick, white-cross” cursor over cell A2, then click in cell A2, hold the

click, and drag your cursor to cell J9. This is how you highlight a range. The

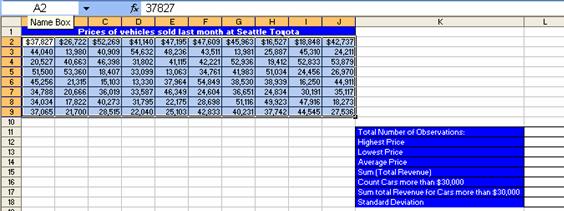

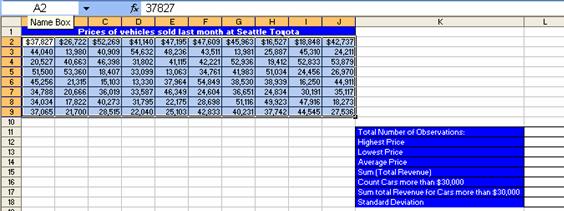

range you have highlighted is A2:J9. (Figure 89):

Figure 89

43. Click in

the Name Box (Figure 90):

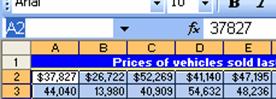

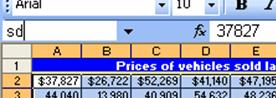

Figure 90

44. After you

click in the name box it will highlight the cell A2.

45. Type over

“A2” and replace it with “sd” (“sd” will stand for sales data). (Figure 91):

Figure 91

46. Then hit

Enter to register the newly named cell range. The cell range A2:J9 now has the

name “sd” When we create functions that look at that range we can now simply

type in “sd” instead of highlighting the range A2:J9

47. Click in

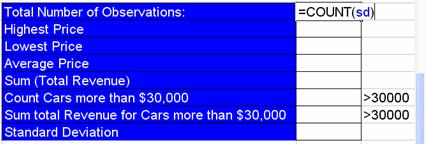

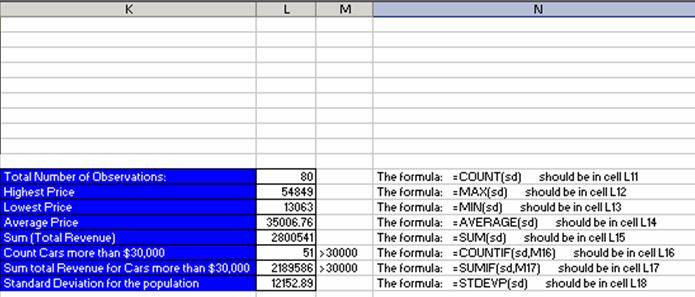

cell L11 and see if you can find a function that can count the number of cars

that were sold last month at Seattle Toyota. When you find it, your formula

result should look like this (Figure 92):

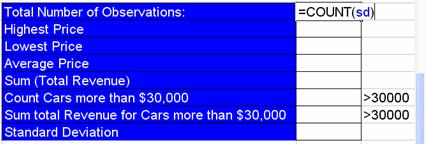

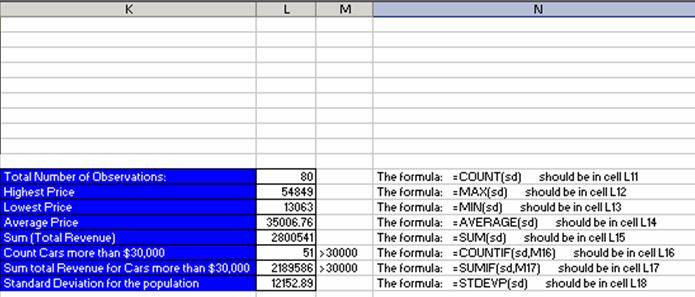

Figure 92

48. See if you

can find the remaining functions using your new “function hunting skills”

49. When you

are done you should see the same results that you see in column L in Figure 93 by using the formulas that you see in column

N in Figure 93.

Figure 93

50. We have

been using cell references so often, that it is now time to investigate the

different types of cell references è

When we copy formulas that contain

cell references to other cells, then we need to understand that there are four

types of cell references:

1. Relative

2. Absolute

3. “Mixed

with Column Locked”

4. “Mixed

with Row Locked”

It will only be possible to

understand these if we look at a few examples. Nevertheless, here are the

crucial facts about cell references:

1.

Relative Cell References A1

No

dollar signs

Moves relatively

throughout copy action

2.

Absolute Cell References $A$1

Dollar

signs before both:

Column

designation = A

Row

designation = 1

Remains

locked on cell A1 throughout copy action

“Locks cell reference

when copying it horizontally and vertically”

3.

“Mixed with Column Locked” $A1

Dollar

sign before column designation

Remains

locked when copying across columns

Remains

relative when copying across rows

“Locks cell reference

when copying it horizontally, but not vertically”

4.

“Mixed with Row Locked” A$1

Dollar

sign before row designation

Remains

locked when copying across rows

Remains

relative when copying across columns

“Locks cell reference

when copying it vertically, but not horizontally”

Keyboard shortcut F4 key: Toggles between the four types of cell

references

5.

When creating formulas with cell references, ask two

questions of every cell references:

Q1:

What do you want it to do when you copy it horizontally

Is

it a relative reference?

Is

it a “locked” reference?

Q2:

What do you want it to do when you copy it vertically

Is

it a relative reference?

Is

it a “locked” reference?

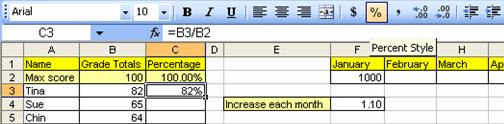

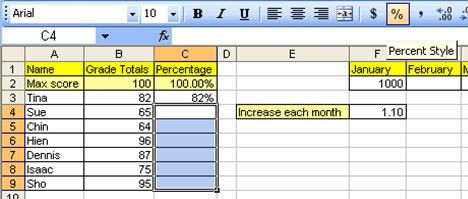

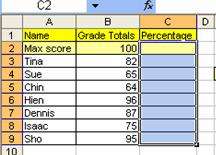

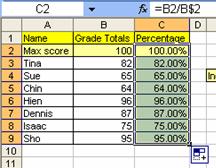

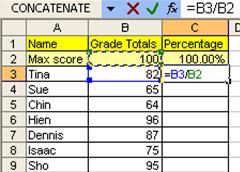

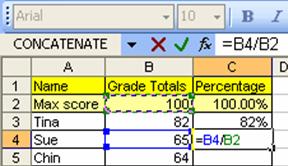

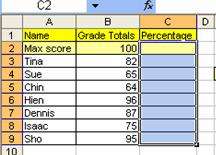

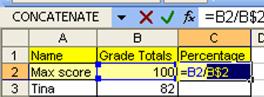

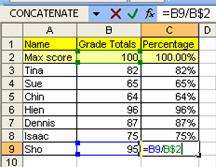

Here are the steps to

learn about the four cell references:

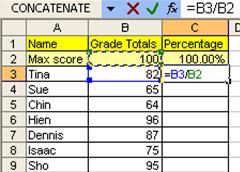

1. Go

to the sheet tab named “Cell References” and click in cell C3 and create the

formula shown in Figure 94. The formula

calculates a proportion or percentage of the whole (depending on how it is

formatted). In our example we are comparing Tina’s score (82 parts of the 100

whole) and comparing it to the total possible points (100 points – the whole).

If you look ahead to creating the formulas for Sue and Chin and Hien, all their

“parts” will have to be compared to the “whole”.

Figure 94

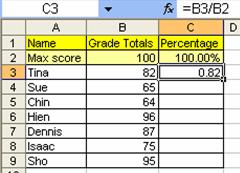

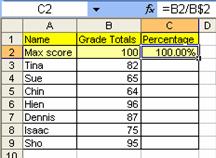

2. Hold

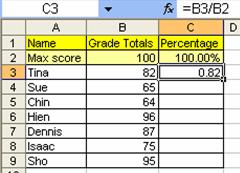

Ctrl, then tap Enter. You should see that the proportion of points that Tina

earned is .82 (Figure 95):

Figure 95

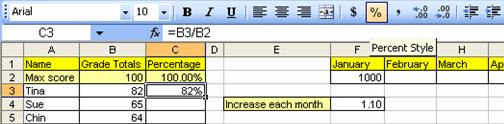

3. To

format the number “.82”

as a percentage, highlight cell C3, click the % button on the formatting

toolbar (Figure 96). Remember 82% is not

a number. Underneath in Excel’s code (just like any other calculator), Excel

sees the number “.82”

even though it is formatted with a % symbol and even though what we see in the

spreadsheet is 82%:

Figure 96

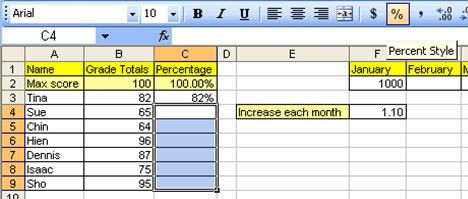

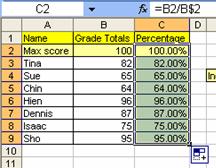

4. Highlight

the range C4:C9 and then click the %button on the formatting toolbar: this

pre-formats the cells with the percentage format (Figure 97):

Figure 97

5. Click

in C4 and create the formula for calculating Sues’ percentage grade (Figure 98):

Figure 98

6. Continue

until you have created the percentage grades (Figure 99):

Figure 99

7. What

we just completed did not require that we know anything about the four

different cell references. However, what we did was inefficient. There is a way

to create all those formulas by just creating one formula in cell C2 and then

copying it down through our range. We will have to learn how to “LOCK” or make

“ABSOLUTE” some of our cell references. If we can learn how to do this, it will

make tasks such as this easier to complete and will result in few errors. In

addition, many of the most advanced Excel Features and tricks are only possible

if we learn about these four cell references.

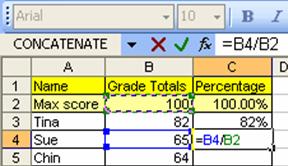

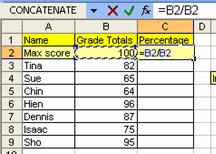

8. Highlight

the range C2:C9 and then hit the delete key (Keyboard short cut: Delete key = delete cell

content but not format) (Figure 100):

Figure 100

9. Click

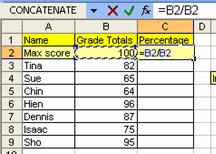

in cell C2 and create the following formula (Figure 101):

Figure 101

10. Now think

about this: the numerator B2 needs to always look one cell to my left and the

denominator B2 always needs to be locked on B2. We have to let Excel know that

the two B2s are different. (If you don’t remember the difference between

numerator and denominator use Google’s definition feature to look these words

up).

the

numerator B2 needs to always look one cell to my left

i.

This is called a relative cell reference

ii.

Relative to the cell the formula sits in, the cell reference

always needs to look one cell to the left

iii.

For our example the “one-to-the-left” B2 will be

entered into the formula as B2

the

denominator B2 always needs to be locked on B2

i.

This is called a LOCKED or ABSOLUTE cell reference

ii.

The secret code we need to put into our cell reference

to let Excel know that the cell is locked in the “$” sign. Why the dollar sign?

No reason – just think of it as the secret code).

iii.

But where do we put the secret code? The answer depends

on which direction you will be copying the formula. In our case we will be

copying up-and-down, across the rows (and rows are numbers), so the secret code

goes in front of the Number 5

iv.

For our example the “LOCKED” B2 will be entered into

the formula as B$2

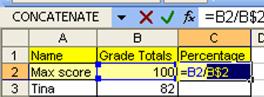

11. Very

carefully, place your cursor in the middle of the denominator B2 and click the

F4 key twice (Figure 102):

Figure 102

12. Hold Ctrl,

then tap Enter. You should see this (Figure 103):

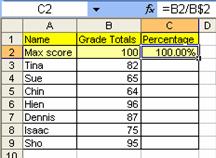

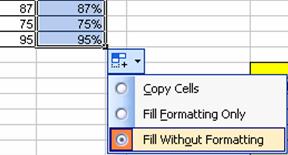

Figure 103

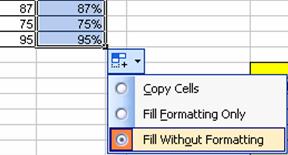

13. Point to

the fill handle and with your angry rabbit copy the formula down to cell C9 (Figure

104):

Figure 104

14. Notice that

it copied the yellow cell fill-color formatting down with the formula. Take you

cursor and click on the blue smart tag, then click on Fill Without Formatting

(this great feature copies only the formula) (Figure 105):

Figure 105

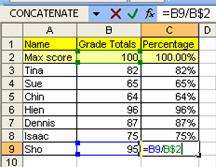

15. Click in

cell C9 and audit the formula to make sure that you actuality did create 8

formulas, but only had to create one formula which you then copied down (Figure

106):

Figure 106

16. Click in

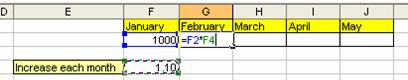

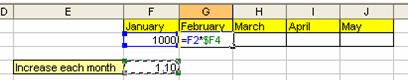

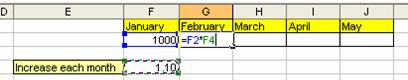

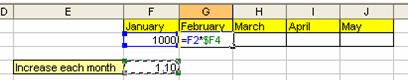

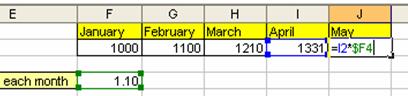

cell G2 and create the formula seen in Figure 107.

Because the January 1000 amount will be increased by 10% each month, we need to

multiply (1 + .10) or 1.10 by each previous month’s amount. But notice that the

cell reference F2 is actually always going to be looking at the cell “one-to-the-left”

(relative cell reference = F2) and the cell reference F4 will always be

“locked” on F4 when copying it side-to-side, across the columns (columns are letters),

so the secret code goes in front of the letter (locked copying it across the

columns = $F4)

Figure 107

17. Very

carefully, place your cursor in the middle of the F4 and click the F4 key three

times (Figure 108):

Figure 108

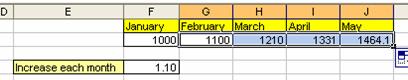

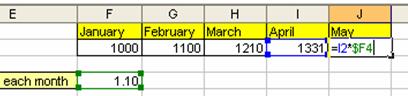

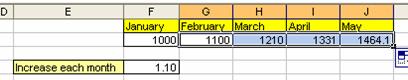

18. Hit Ctrl +

Enter. Point to the fill handle and copy to formula to J2 (Figure 109):

Figure 109

19. Click in

cell J2 to audit the formula with the F2 key (Figure 110):

Figure 110

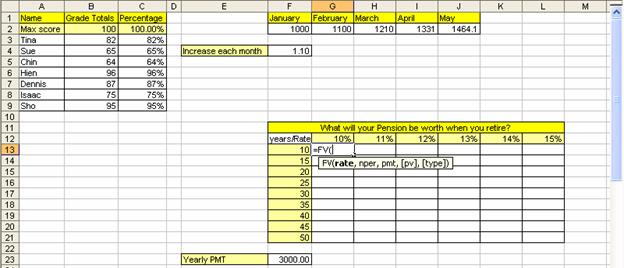

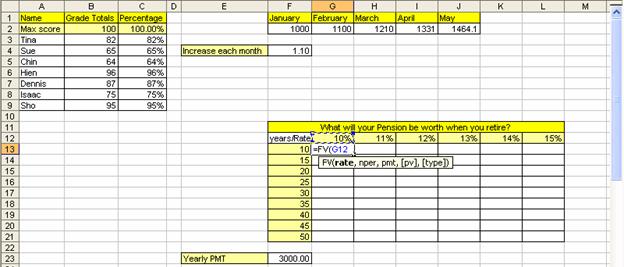

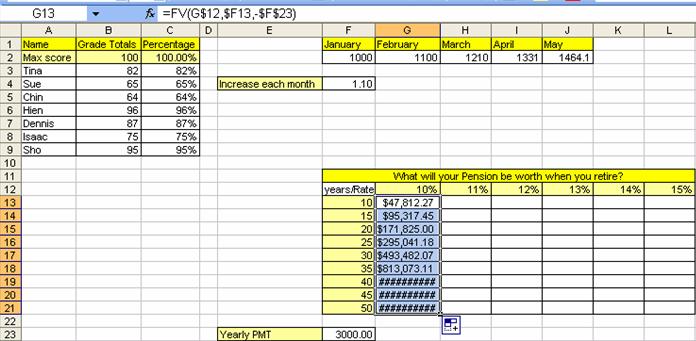

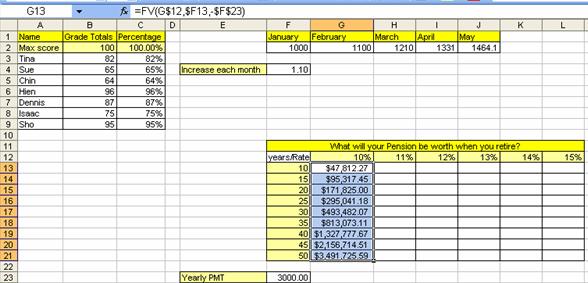

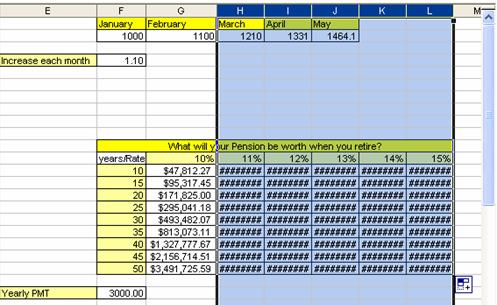

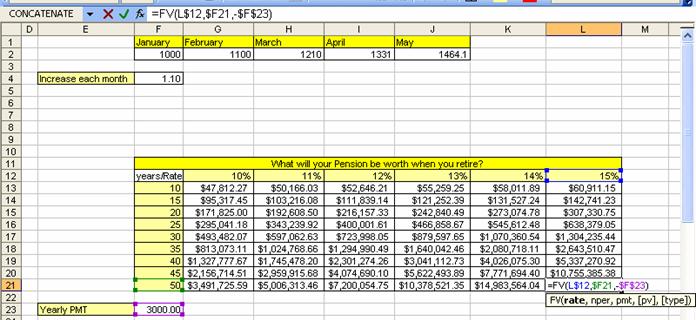

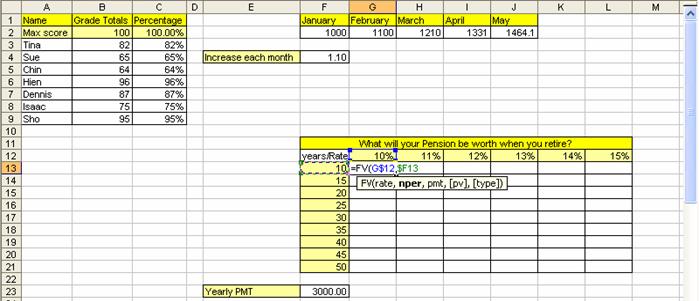

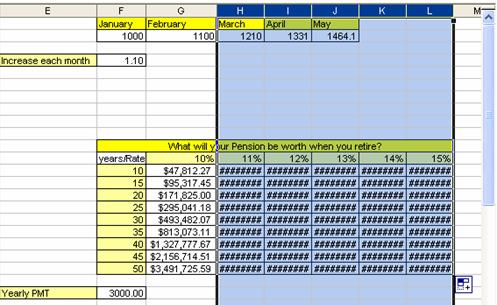

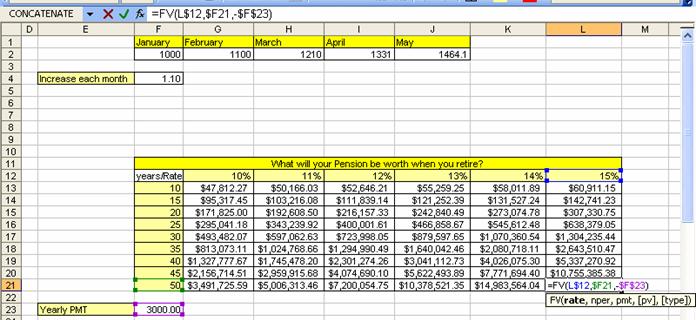

20. Look in Figure

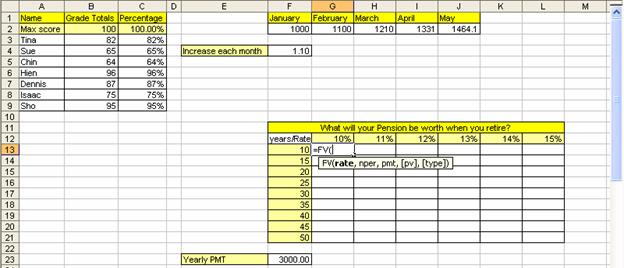

111 at the table titled “What will your

Pension be worth when you retire?” We would like to estimate what our pension

will be depending on the annual rate that we earn and how many years we save

for retirement. The trick here is that we don’t want to type 54 formulas. We

would like to create the whole “sea of formulas”, G13 to L21, by creating only

one formula in cell G13 and then copying it to the remaining cells.

21. Click in

cell G13 and type “=FV(“. The screen tip will come up to help you with the arguments

for this function. To calculate our retirement funds we will need to assume an

annual rate “rate”, the number of

years that we deposit money “nper”

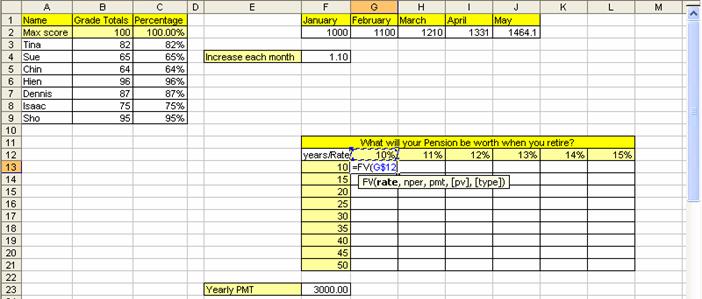

and a yearly deposit amount “pmt” (Figure

111):

Figure 111

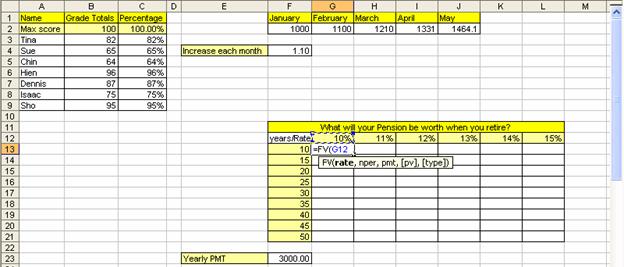

22. Click on cell

G12 (Figure 112):

Figure 112

23. Can you see

in Figure 112 that we will need to use

the 10% for all the formulas in column G? Can you also see that when we copy

the formula over to column H we need to use the 11%? This means that we need

the cell reference locked (absolute) when we are copying the formula down, or

vertically, or across the rows: the row reference needs to be locked! However,

when we copy the formula to column H the cell reference should not be

locked (absolute) when we are copying

the formula to the side, or horizontally, or across the columns. The column

reference is not locked: it is relative.

24. Because we

want to lock (absolute) this cell reference when we copy the formula down, across

the rows, we need the “$” sign in front of the number. Because we want this

cell reference to move relatively as we copy the formula to the side, across

the columns, we do not need the “$” sign in front of the letter. Cell reference

= G$12 è

hit F4 twice (Figure 113):

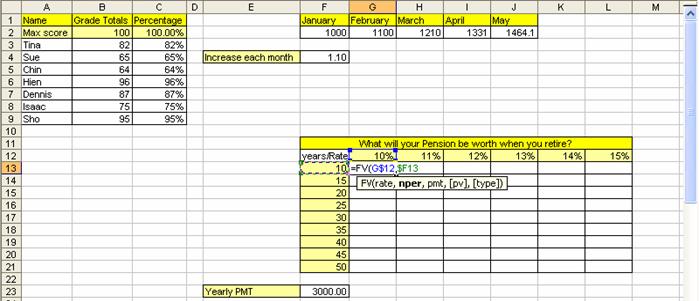

Figure 113

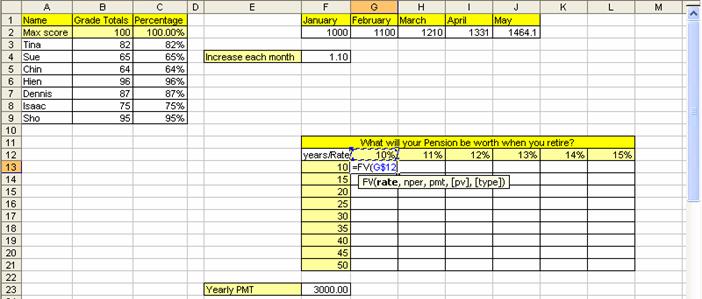

25. Type a

comma, click on F13, and hit F4 three times.

26. We hit F4

three times because we want this cell reference to move relatively as we copy

the formula down, across the rows, and we want the cell reference locked

(absolute) as we copy the formula to the side, across the columns. Cell

reference = $F13 è

(Figure 114):

Figure 114

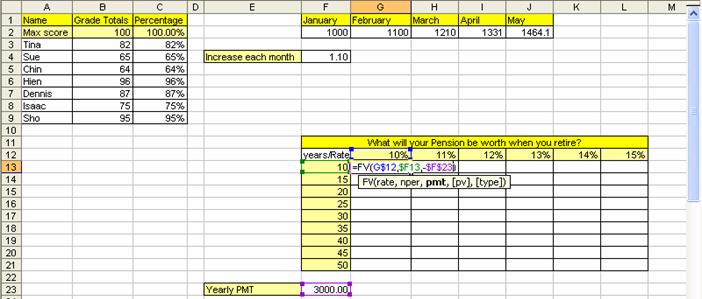

27. Type a

comma, type a minus sign, click on cell F23, and hit F4 once, type a close

parenthesis.

28. Because we

want to use the cell reference F23 in every cell when we copy this formula, we

want the cell reference locked in all directions. The dollar sign in front of

the column reference “F” locks the cell reference when copying the formula to

the side, across the columns. The dollar sign in front of the row reference “23” locks the cell reference

when copying the formula down, across the rows. Cell reference = $F$23 è

(Figure 115):

Figure 115

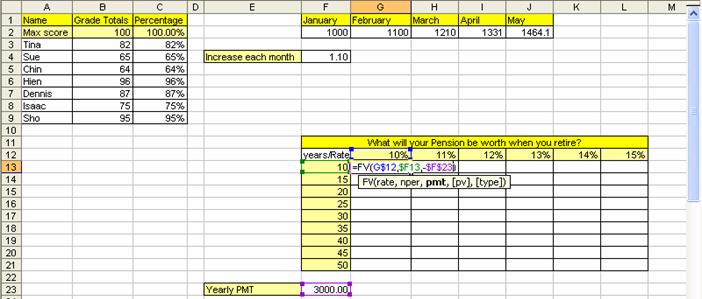

29. Hold Ctrl, and

then tap Enter. Point to the fill handle and click and drag formula down to

cell G21 (Figure 116):

Figure 116

30. Don’t be

alarmed by the pound signs. They are just saying: “Please expand the column so

this big number has room to show itself.” Point between the two column headings

G and H and double click to expand the columns. You should see this (Figure 117):

Figure 117

31. Now point

to the fill handle in the lower right corner for the entire range, then click

and drag to L21. Notice that many pound signs appear. Highlight the column

headings from H to L by clicking on the columns heading H and dragging to L.

Then double-click between the column headings H and I to expand the columns (Figure

118):

Figure 118

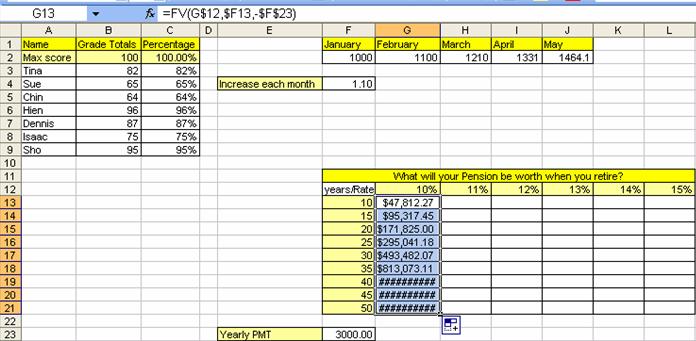

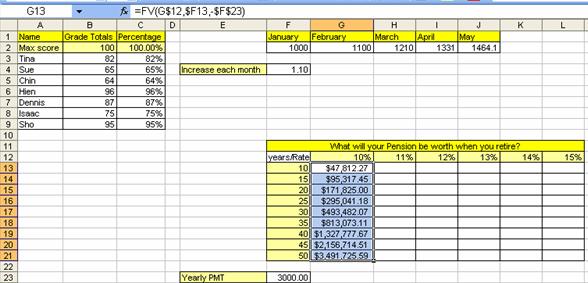

32. Our result

is that 54 formulas were created by enter just one formula, adding the correct

cell references and then copying the formula in two-steps (first down, then

over) (Figure 119):

Figure 119

33. For more

practice with cell references, click on the sheet tab named “Multiplication

Table and see if you can create 144 formulas by enter just one formula, adding

the correct cell references and then copying the formula in two-steps.

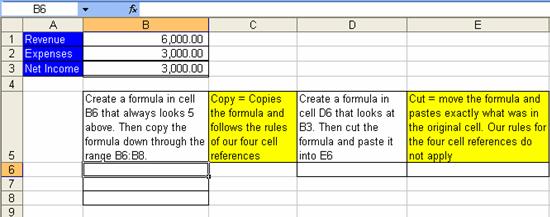

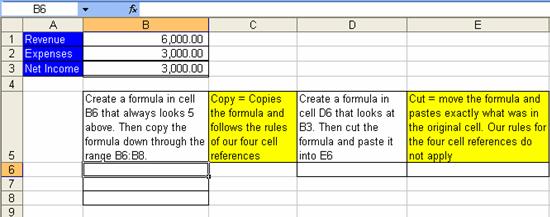

In the last few examples we saw what

happens to cell references when we copy a formula that has cell references. Now

we need to see what happens when we move a formula that contains cell

references. Copy means copy the formula from a cell or range of cells, leave

the formula in the original location, and then paste the formula in some other location.

Move means cut the formula from a cell or range of cells, it will no longer be

located in the original location, and then paste the formula in some other location.

Here are the steps to

learn about the difference between copying and moving a formula with cell

references.

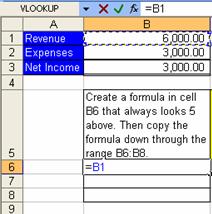

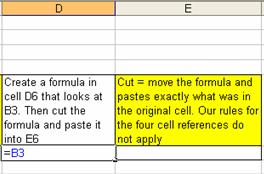

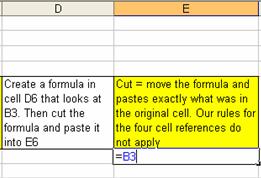

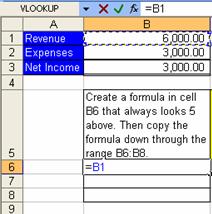

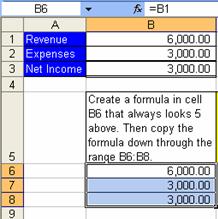

1. Click

on the sheet tab named “Copy and Move.” Click in cell B6 and follow the

instructions listed in cell B5 (Figure 120Error!

Reference source not found.):

Figure 120

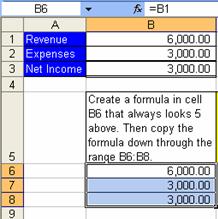

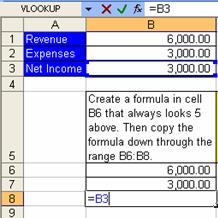

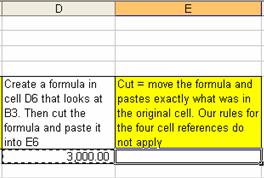

2. Figure

121, Figure 122 and Figure 123 illustrate

that when you copy a cell reference that has a relative cell reference component,

the cell reference changes relatively. In Figure 121 we see a formula that is looking into cell B1. In Figure 123 we see a formula that is looking into cell

B3. When we copied the formula, the cell reference moved relatively – it

actually did exactly what we told it to do, namely, “always look five above”.

Figure 121

Figure 122

Figure 123

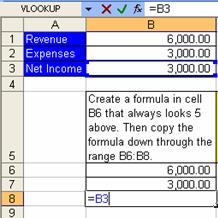

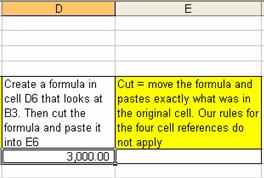

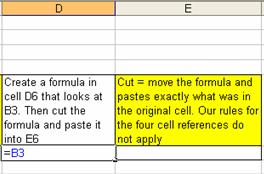

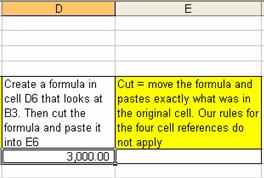

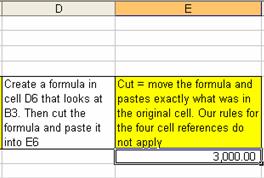

3. Now

let’s look at what happens when we cut a formula with a relative cell reference

and paste it somewhere else.

4. Click

in cell D6 and create the formula “=B3” (Figure 124):

Figure 124

5. Hold

Ctrl, then tap Enter (Figure 125):

Figure 125

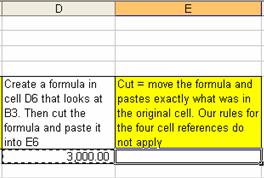

6. Ctrl

+ X, hit Tab (Figure 126):

Figure 126

7. Ctrl

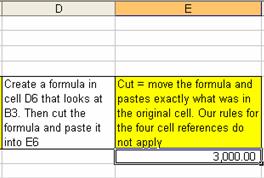

+ V (Figure 127):

Figure 127

8. Hit

F2 (Figure 128Figure 127):

Figure 128

9. Compare

Figure 124 and Figure 128. When you cut a formula with a relative

cell reference component and paste it into a new cell, the formula does not

change – it actually moves the cell references exactly as they were in the

original cell and pastes them in the new location. This is because when you

move, you do not change anything; you simply put the formula, intact, in a new

location.

10. Wow!

Knowing the difference between moving and copying formulas is very helpful in

our pursuit of efficient spreadsheet construction. Let’s practice copying a

formula with relative cell references another time before we move on to the

next topic è

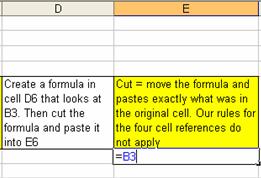

11. Navigate

back to the sheet tab named “The Equal Sign” by holding the Ctrl key, and then

tapping the PageUp key nine times (=SQRT(81) times in Excel speak). You should

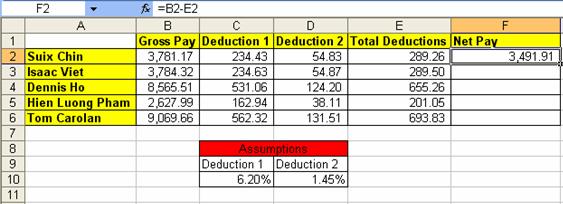

see this (Figure 129):

Figure 129

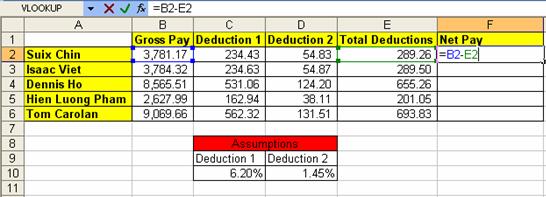

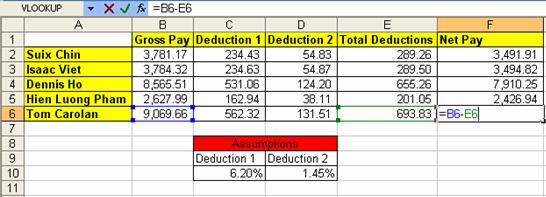

12. Click in cell F2. Hit the F2 key (Figure 130). Look at

the formula in cell F2. Can you say what type of cell references they are? Can

you say what will happen to the formula when you copy it down from F2 to F6?

The formula in cell F2, “=B2-E2”, uses relative cell references and so when you

copy it down the cell references will move relatively. The formula actually

reads: “always look four to the left and subtract one to the left”.

Figure 130

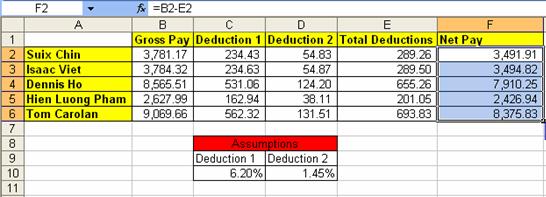

13. Hold Ctrl,

then tap the Enter key. Point to the fill handle and with your cross hair

(angry rabbit), double click. The double click on the fill handle with your

angry rabbit (cross hair), tells the formula to copy down as long as there is

cell content in the cell directly to the left (Figure 131):

Figure 131

14. Click in

cell F6 and hit the F2 key (Figure 132).

Because the cell references are relative and because we copied the formula, the

formula, “=B6-E6”, looks different, but really it is the same formula, namely:

“always look four to the left and subtract one to the left”.

Figure 132

15. Look at Figure

132. What is the word “Assumptions”

across C8 and D8 mean?

16. Click the

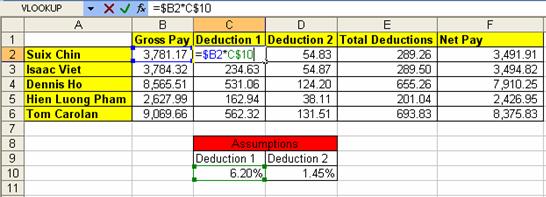

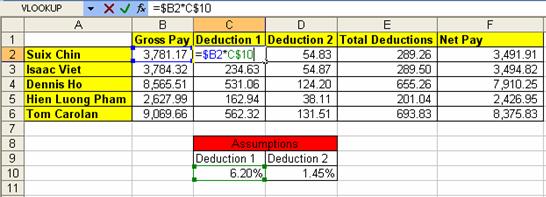

Esc key to remove the range finder in cell F6. Click in cell C2 and then hit

the F2 key (Figure 133). We can see in

our formula that Deduction 1 is calculated by taking Suix Chin’s Gross Pay and

multiplying it by the tax rate of 6.20%. Because the tax rate of 6.20% can

change we have placed it in a cell and had our formula refer to it using a cell

reference. We have assumed that our tax rate is 6.20% and thus have placed it

into an assumption table. In our next section we will discuss the amazing power

of assumption tables: when to use them, what to put in them and how to properly

orientate them!

Figure 133

Our golden rule for assumption tables is: All data that can

vary (variable data) goes into a properly orientated assumption table. An

example of data that can vary is a tax rate. An example of that data that will

not vary is 12 months in a year. Remember: we don’t want to type data that can

very into a formula for three reasons: 1) It is easier to edit or change our

formula later if the variable data it is not typed into the formula (example: tax

rate changes), 2) It is more polite for the spreadsheet user if the variable

data can be seen on the face of the spreadsheet. (For example, even if we were

to create a formula with variable data typed into the formula (such as

“=$B2*.062”), when we came back tomorrow to use the worksheet, we as the

creator might not even remember which formulas have variable data and/or what

the variable data is). 3) what-if or scenario analysis is significantly easier

when an assumption table is used. What-if/scenario analysis is simply when you

change the variables to see different results.

In addition to the easy with which we can edit or locate

variable data, assumption tables that are properly orientated can reduce the

number of formula that we will be required to type into our spreadsheet. Proper

orientation means the labels in the main table are orientated (horizontally or

vertically) in the same way as the labels in the assumption table, and that

there is at least one blank row or column between the main table and the

assumption table. Also, you can format the assumption table differently to

distinguish it from the main table.

In this section about assumption tables we will learn:

1. When

to use them

2. What

to put in them

3. How

it is easier to locate and edit variable data

4. How

to properly orientate them!

5. See

the ease with which we can conduct What-if/scenario analysis

6. Bask

in the amazing power of assumption tables!!

It will help if we work through an example è

Here are the steps to

learn about assumption tables:

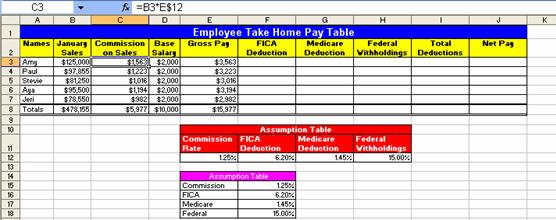

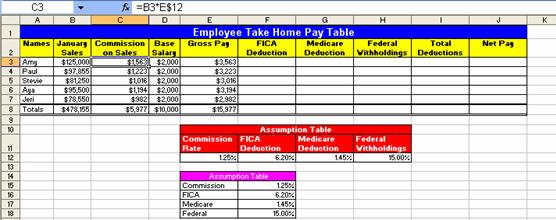

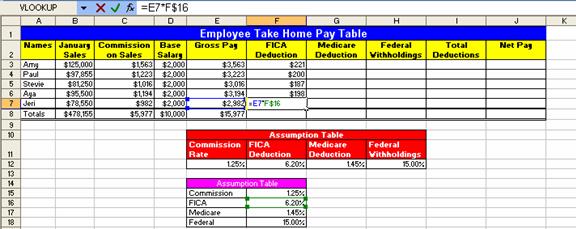

1. Navigate

to the sheet tab named “Assumptions” (Figure 134).

This table will be used to calculate the Net take home pay for a number of

employees. Notice that the calculated amounts for Commission on Sales, and

Gross Pay have already been calculated. Our goal is to calculate the three

payroll deductions (FICA, Medicare, and simplified Federal) and the Net Pay.

Figure 134

2. Click

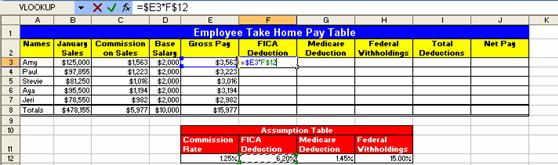

in cell C3 and hit the F2 key. We can see the formula “=B3*E$12” ( Figure 135). Our first question we want to answer is:

when do we use an assumption table? We use an assumption table when our formula

contains variable data such as a tax rate. In cell E3 we are calculating the

commission on sales that we pay each employee. Can this commission rate change?

You bet!

Figure 135

3. Hit

the Esc key. Click in cell E12. Our second question is: what do we put into an

assumption table? We put the variable data that we need for our formula into an

assumption table. In Figure 136 we can

see that the commission rate of 1.25%, which we used in our formula, has been

placed into an assumption table. This enables easy editing and formula updating

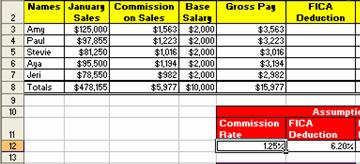

later. Now, imagine that the boss just gave everyone a raise from 1.25%

commission to 2% è

Figure 136

4. Our

third question is: How easy is it to locate and edit variable data? Very easy!

5. Type

2, then hit Enter (because the cell was preformatted with the percent style, we

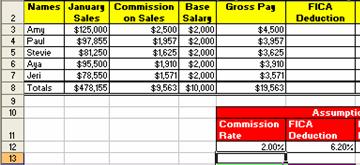

did not have to type the % symbol). You should see the entire column of “Commission

on Sales changes (Figure 137). THAT WAS

EASY!! It is easier to change the variable data when it is on the face of the

spreadsheet that it is to look for it, hidden underneath, inside a formula! I

can already feel that vacation time adding up with all the time I will be

saving!

Figure 137

6. Click

in cell E12 and change the rate back to 1.25%. Our goal is still to calculate

the deductions and calculate take home pay

7. Click

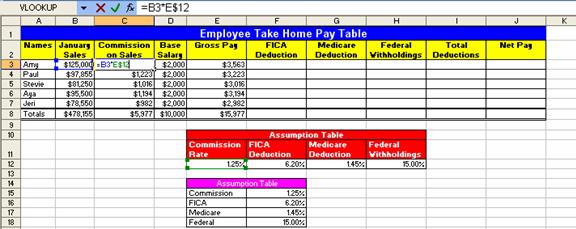

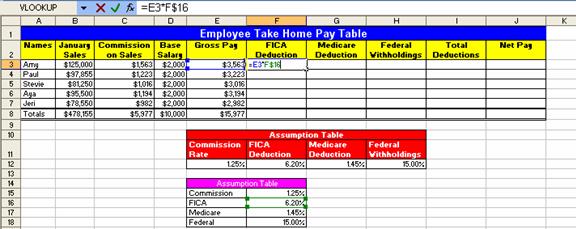

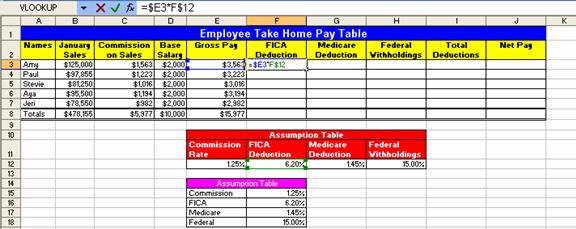

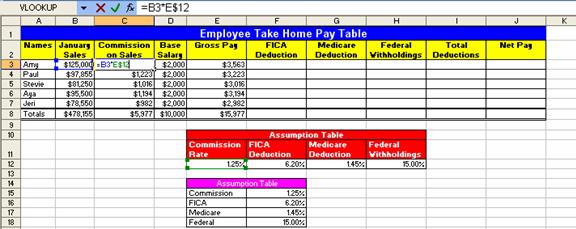

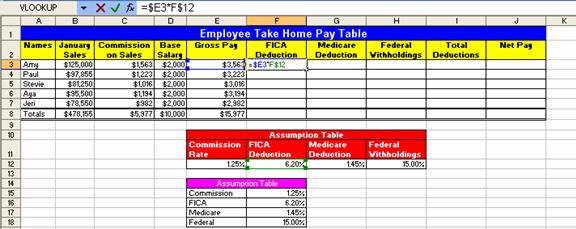

in cell F3 and create the formula for calculating the FICA deduction. But wait!

Which assumption table should we use?

8. Is

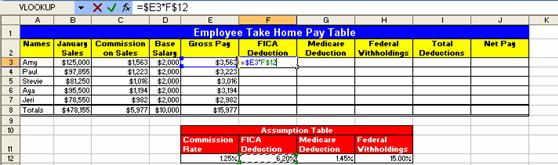

the formula “=E3*F$16” (Figure 138) the

one to use?

Figure 138

9. Or

is the formula “=$E3*F$12” the one to use?

Figure 139

10. The answer

to which formula to use (which formula is more efficient) leads to the fourth

question: what is the proper orientation for our assumption table? If we were

to use the formula as seen in Figure 138,

“=E3*F$16” we would have to create three separate formulas to make all our

deduction calculations. If we were to use the formula as seen in Figure 139, “=$E3*F$12” we would have to create only

one formula to make all our deduction calculations. This sort of efficiency is

exactly what we are striving for. But why does the formula using the variable

data from the assumption table that is orientated horizontally allow us to

create only one formula that will work for all our deductions? To see this,

let’s try both formula and see which works best.

11. You should

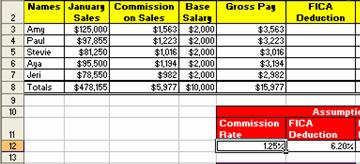

still have cell F3 highlighted. Create this formula: “=E3*F$16” (Figure 140):

Figure 140

12. Hold Ctrl,

then tap Enter. Point to the fill handle, and with the Angry Rabbit cursor,

copy the formula down through the range

F3:F7. Then click in cell F7 and hit the F2 key (Figure 141). You can see that the formula worked when we copied it down.

Figure 141

13. Hit Esc. Click

back into cell F3. Copy the formula to cell G3. Click in cell G3 and hit the F2

key to show the Range Finder. In Figure 142

we can see that the range finder shows that the cell reference for our tax rate

moved and is now looking into the cell G16. Because the orientation of the

assumption table is vertical (the labels for FICA, Medicare and Federal are located

one on top of the other) and the orientation of our main table is horizontal,

we would have to create three individual formulas in the cells F3, G3 and H3.

Notice that in Figure 142 that the range

finder moved to the right when we copied our formula to the right. This

indicates that if we had used the horizontally orientated assumption table that

formula would have calculated correctly è

Figure 142

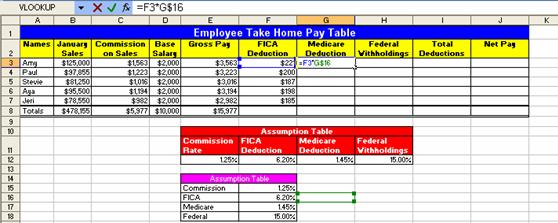

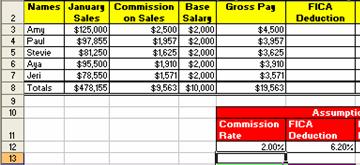

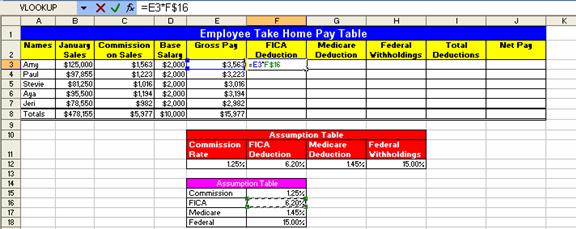

14. Click Esc.

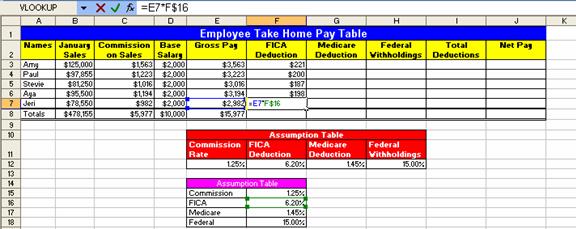

Then Hold Ctrl, and tap the Z key three times (undo). Then create the formula “=$E3*F$12”

in cell F3 (Figure 143):

Figure 143

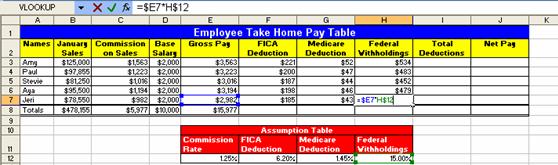

15. Hold Ctrl,

tap Enter. Ctrl + C (to copy formula). Hold Shift, then tap the Down Arrow key

4 times and the Right arrow key 2 times (highlights the range). Ctrl + V (pastes

formula). Click in cell H7 and hit the F2 key. In Figure 144 we can see that because we orientated our

assumption table correctly, it worked like MAGIC! We created the sea of

formulas in the range F3:H7, 15 formulas, but we only had to type in one formula!

This sort of efficiency is our goal!

Figure 144

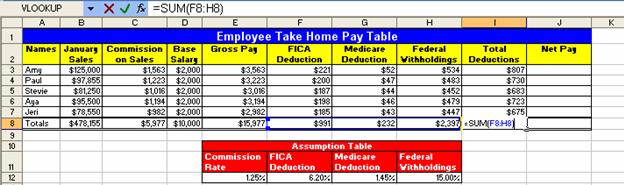

16. Hit Esc.

Highlight the range F3:I8. Hold Alt, and then tap the Equal sign key “=” (Alt +

= is keyboard shortcut for AutoSum). As you can see in Figure 145, by highlighting a range of values and one

blank row below and to the right, the Auto Sum feature knew what to add up. It

doesn’t always add up the correct amount, so let’s check to be sure. After

selecting cells with the AutoSum and verifying, the last cell we will check is

cell I8 (Figure 145):

Figure 145

17. Highlight

the range J3:J8 (Figure 146). Notice that

when you highlight a range that one of the cells is white and the rest are a

light steel-blue color. The white cell is waiting for you to put a formula into

it. If you put a formula into cell J3 and then hold Ctrl and tap Enter, you

formula will go into all the cells highlighted è

Figure 146

18. Create the

formula that will always take the value “five to the left and then subtract one

to the left in cell J3. Type ‘=”, tap the left arrow key five times, Type “-“,

tap the Arrow key once. You should see this (Figure 147):

Figure 147

19. Hold Ctrl, and

then tap Enter. We see here that if you

have a range highlighted and you place a formula into the white cell, when you

hold Ctrl and tap Enter, the formula is placed into all the cells that are

highlighted! You should see this (Figure 148):

Figure 148

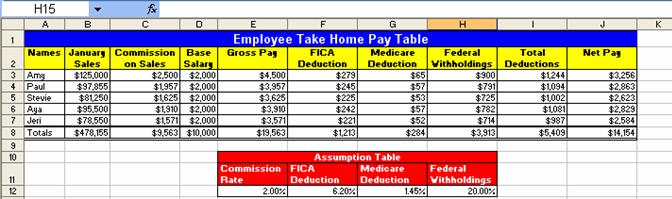

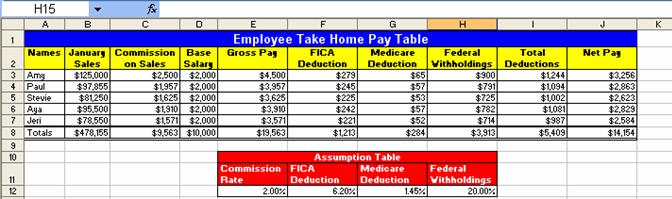

20. Our fifth

question is: How easy is what-if/scenario analysis when we use assumption

tables?

21. Click in

cell E12 and change the Commission rate to 2%. Click in cell H12 and change the

simplified Federal Withholding rate to 20%. Can you see how easy it is to say:

“What if I changed this; what would happen to our calculations and our

results?” (Figure 149):

Figure 149

22. is hidden

underneath, inside a formula

23. Our final

question about assumption tables is how can we bask in the amazing power of

assumption tables?

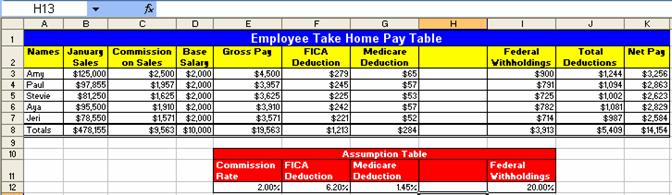

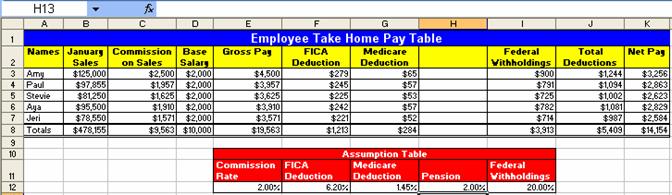

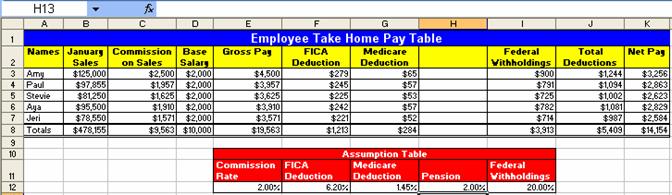

24. Imagine your

boss comes in and says: “we just added a new 2% deduction can you update our

calculating table?” You look over your shoulder and say: “Oh you mean like

this?!!” And with blistering speed you complete these steps è

25. Click in

column H, Click Alt, then tap I and then

tap C (Figure 150):

Figure 150

26. Click in

cell H11 and type Pension. Hit Enter, then type 2% (Figure 151):

Figure 151

27. Highlight

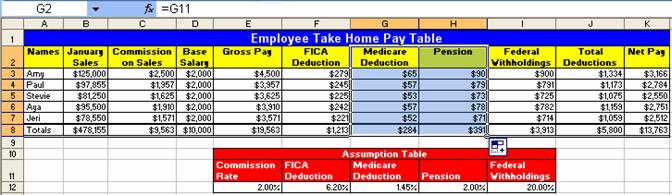

the range G2:G8 and point to the fill handle in the lower right-corner. When

you see your Angry Rabbit, click and drag one column to the right. You are

done! 10 clicks and you have completely updated the table and you have amazed

your boss (who then promptly gives you a promotion)! (Figure 152):

Figure 152

28. In Figure 152 we can see that the deduction formulas

updated because we used a properly orientated assumption table and mixed cell

references; we can see that the SUM function for totals in row 8 updated

because they were always looking to add the five above; and we can see that the

totals for Total Deduction updated when we inserted a column because it

utilized a range in its arguments! Wow, now we can have extra vacation time and

bask in the amazing promotion we received – all because of efficient use of

assumption tables, mixed cell references and range functions!

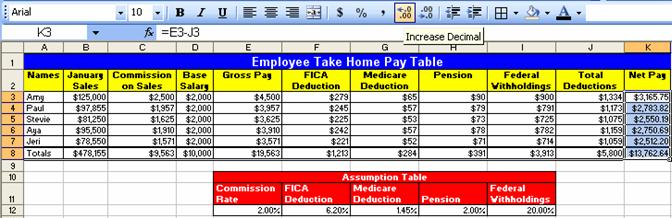

29. Highlight

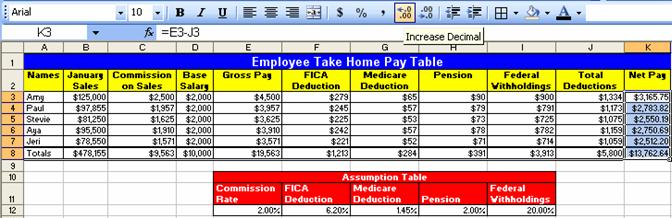

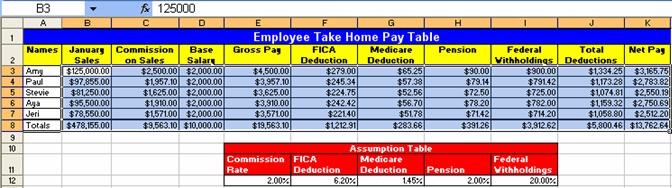

the range K3:K8. Click the increase decimal button twice (Figure 153). Notice that the total Net Pay is $13,762.64.

Figure 153

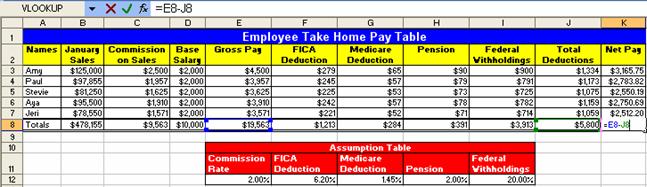

30. Click in

cell K8 and then hit the F2 key (Figure 154).

There is no way that $19,563 - $5,800 = $13,762.64. What is going on here? This

is one of the most common mistakes that people make in Excel. It is our job as

Soon-To-Be Excel Efficiency Experts (EEE), to know that this is caused by

formatting. What we often see in Excel is not actually what sits in the cell.

Figure 154

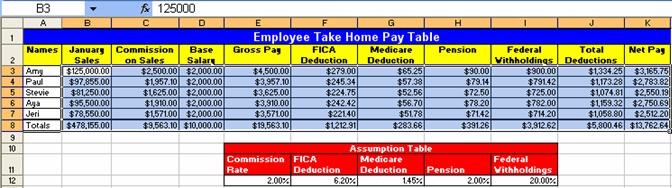

31. To prove to

ourselves that what is in the cell is different than what we are seeing on the

surface of the spreadsheet, highlight the range B3:K8 and click the increase

decimal button twice (Figure 155). We can

see that what was really in the cell was numbers with more decimal places than

we were allowed to see!

Figure 155

32. As you learn to work with Excel you must be

vigilant in the endeavor to always match the proper formatting with what

actually sits in the cell. This leads us to our next section about

formatting.

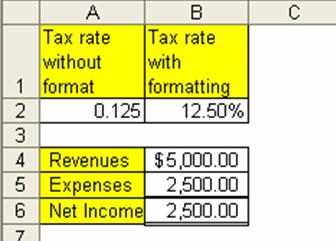

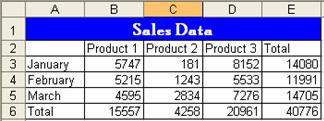

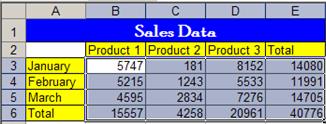

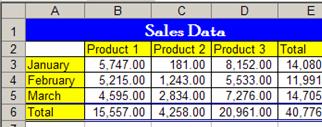

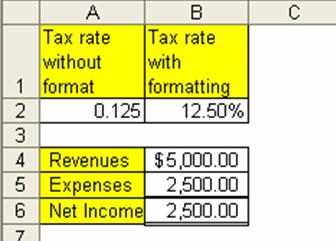

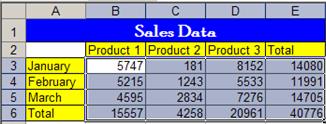

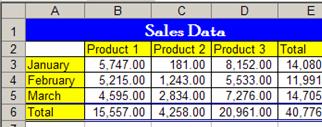

We format cells with color, number

formats (such as currency), borders and other format so that we can better

articulate our message to the viewer of our spreadsheet or printout of the

spreadsheet. For example in Figure 156 we

can see that formatting can help to communicate important information:

1. The

percentage format helps to communicate the number of parts for every 100 parts

2. The

accounting (similar to currency) format indicates that the Revenues, Expenses

and Net Income are in USA

dollars

3. The

double line under the Net Income communicates that this is the “bottom line”.

4. The

color helps to communicate that there are labels indicating what the numbers

mean

Figure 156

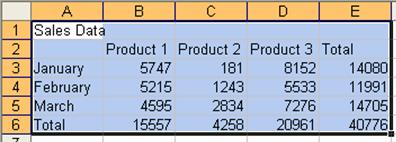

Here are the steps to

learn how to apply cell formatting

1. Navigate

to the sheet named “Formatting (2)”. Click in cell E2. Hold Ctrl, then tap the “*” key on the number

pad (this selects the table) (Figure

157):

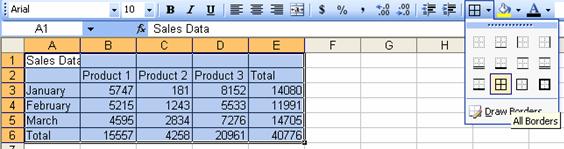

Figure 157

2. Click

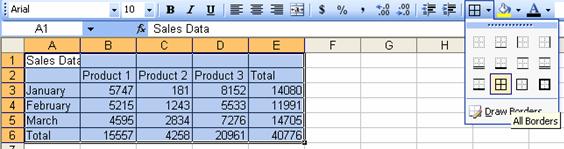

the All Borders button on the Formatting Toolbar ():

Figure 158

Figure 159

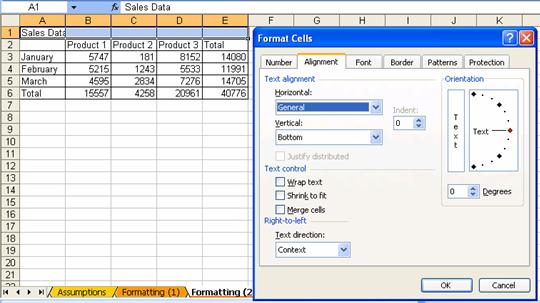

3. Highlight

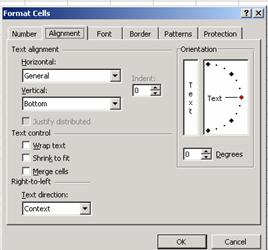

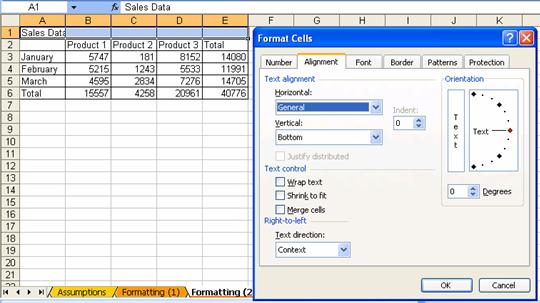

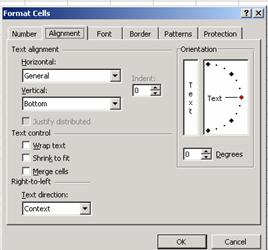

the range A1:E1. Hold Ctrl key and tap “1” key (use the “1” below the F1 key not the “1” on the number pad). Ctrl + 1 opens the Format Cells dialog box

(you could also right-click the highlighted range and point to Format Cells) Once

you have the Format cells dialog box open click on the Alignment tab. See (Figure

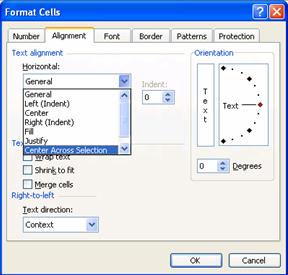

160):

Figure 160

4. With

the Alignment tab selected, click the down arrow under Horizontal and

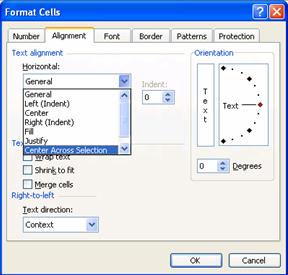

select “Center Across Selection” (Figure 161):

Figure 161

5. We

chose “Center Across Selection” instead of the more widely used “Merge and

Center”. “Center Across Selection” allows move universal structural changes

such as inserting columns/rows and moving, whereas the “Merge and Center”

sometimes will disallow such actions.

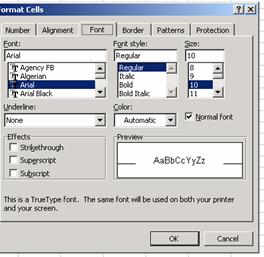

6. Click

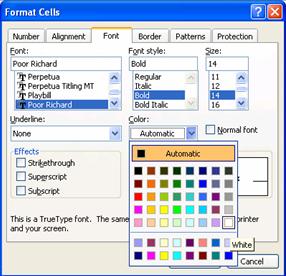

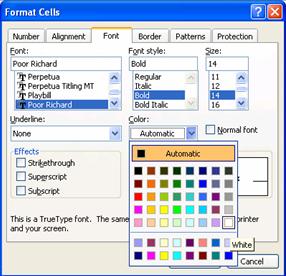

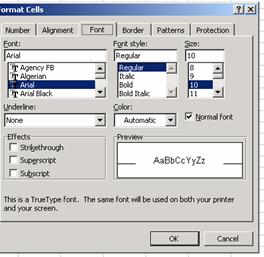

the Font tab. Select “Poor Richard” font (or some other font), Bold style, Size

= 14, Color (of font) = White (Figure 162):

Figure 162

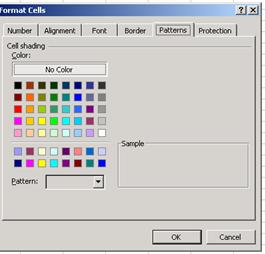

7. Click

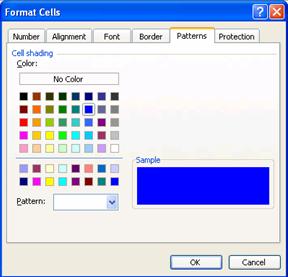

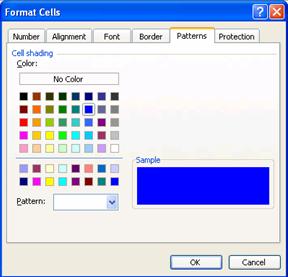

on the Patterns tab and select Blue (Figure 163):

Figure 163

8. Click

OK (Figure 164):

Figure 164

9. Highlight

the rangeB2:E2, Hold Ctrl, Highlight A3:A6. Click the yellow “Fill color button

on the formatting toolbar (Figure 165):

Figure 165

10. Highlight

the range B3:E6 (Figure 166)

Figure 166

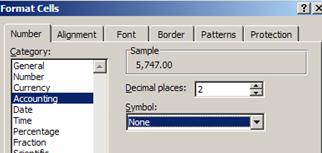

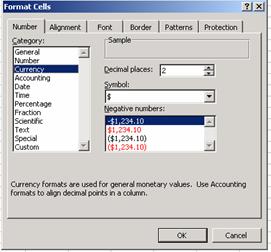

11. Hold Ctrl

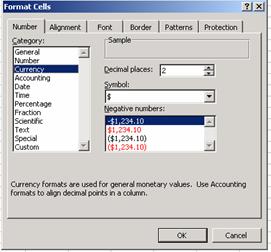

and tap 1. Point to the Number tab. Select Accounting with no dollar sign,

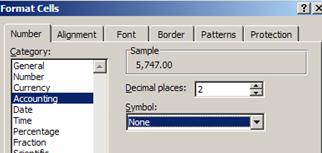

click OK (Figure 167):

Figure 167

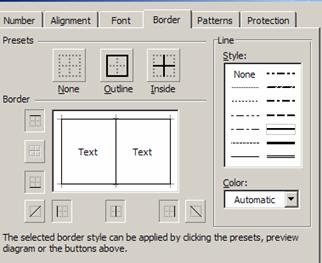

12. Highlight

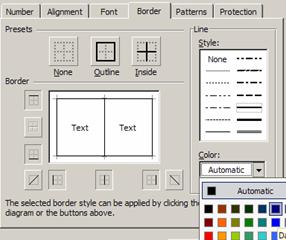

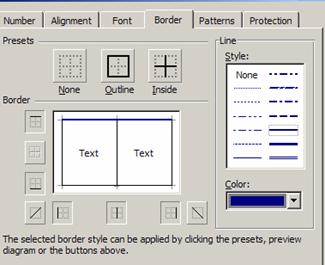

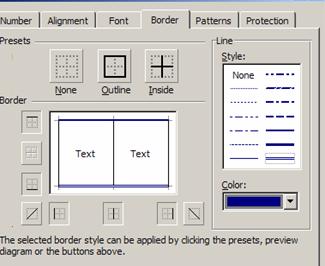

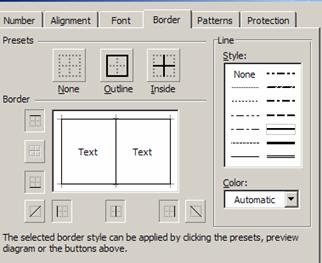

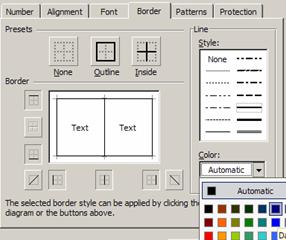

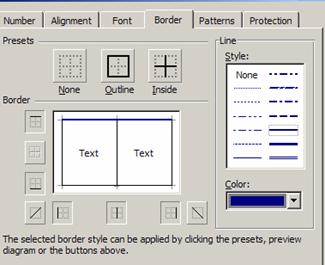

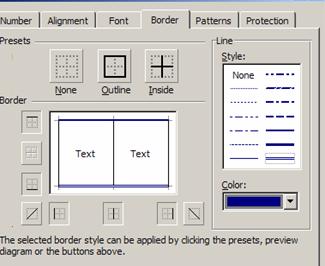

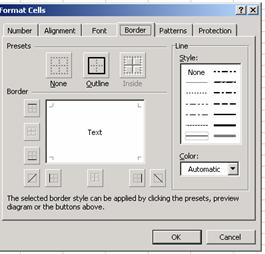

A6:E6, Ctrl + 1, click the Borders tab. In the Line/Styles box, click the

medium thick line (second column, fifth down) (Figure 168):

Figure 168

13. Click

the down arrow under color and select a color (Figure 169):

Figure 169

Figure 170

14. Click the

top line in the Border area (Figure 171):

Figure 171

15. The most

important method that you must memorize to get this tab to work is this: ORDER

MATTERS – you must click Line/Style FIRST, Color SECOND, and then draw your

line the Border area THIRD!

16. Now, use

the method just discussed to add a Navy Blue Double line to the bottom border

of our highlighted range (1):

Figure 172

17. Click OK,

You should see (Figure 173):

Figure 173

18. Now that we

have seen how to apply formatting, we need to look at how formatting can

sometimes trick us. If we are to because efficient with Excel we need to be

able match the proper formatting with

what actually sits in the cell!

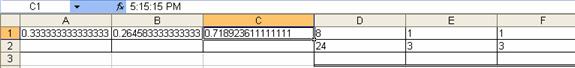

Cell Formatting is the façade that sits on top of data and

formulas. What you see is not always what sits in the cell. For example:

1. If

you see 3.00%, Excel more than likely sees 0.03

2. If

you see $56.70, Excel may see 56.695

3. If

you see 07/26/2005, Excel more than likely sees 38559

4. If

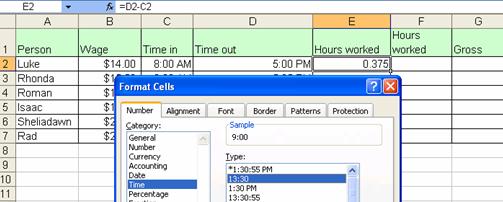

you see 9:30 AM, Excel more than likely sees 0.395833333333333

Let’s look at an example è

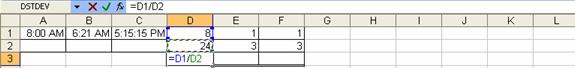

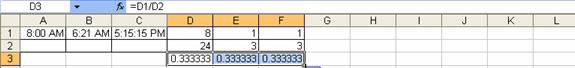

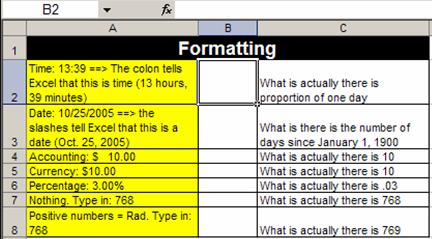

Here are the steps to

learn how to distinguish between formatting and actual cell content!!!!

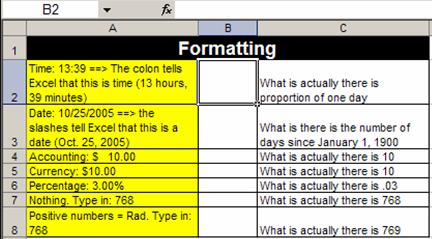

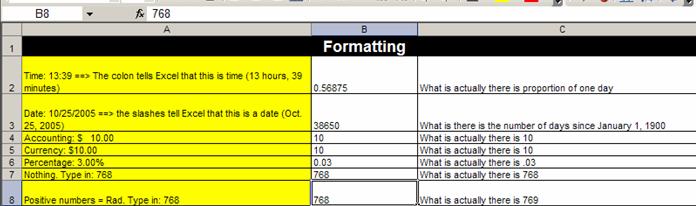

19. Navigate to

the sheet named “Formatting (3)”. You should see what is in (Figure 174). Read the labels in column A and type in

the number in column B. Column C tells you what is actually in the cell. The

key strokes for typing the numbers in are as follows:

i.

B2 è 1, 3, :, 3, 9, Ctrl + Enter (that is to say: Type

the number one, the number three, a colon, the number three, the number nine,

and then hold Ctrl and then tap Enter)

1. Each

time you hit Ctrl + Enter, look at what you see in the cell and compare that to

what you see in the formula bar

ii.

B3 è 1, 0, /, 2, 5, /, 2, 0, 0, 5, Ctrl + Enter

iii.

B4 è 1, 0, Ctrl + Enter (Notice that you did not have to

type in the dollar sign – the cell is preformatted)

iv.

B5 è 1, 0, Ctrl + Enter

v.

B6 è 3, Ctrl + Enter

vi.

B7 è 768, Ctrl + Enter

vii.

B8 è 768, Ctrl + Enter

Figure 174

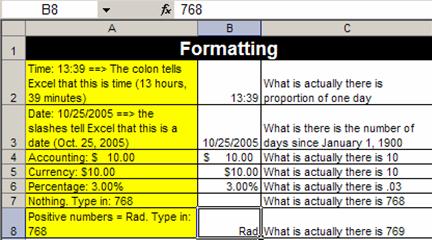

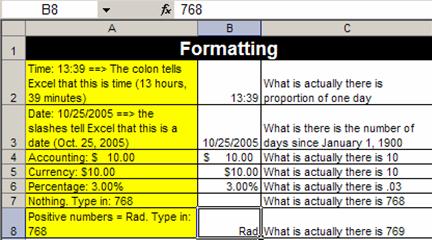

20. When you

are done you should see this (Figure 175):

Figure 175

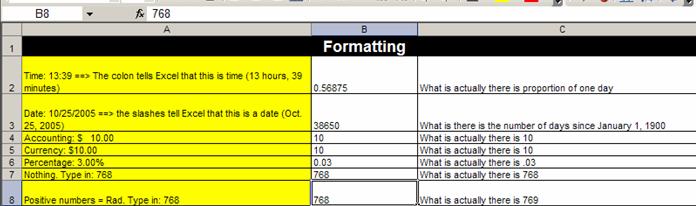

21. Hold Ctrl

and tap ~ key (Figure 176)

Figure 176

22. What you

see in Figure 175 is the façade. What you

see in Figure 176 is what actually is in

the cell and is what Excel will use for any formulas (whether calculating, text

or other formulas)

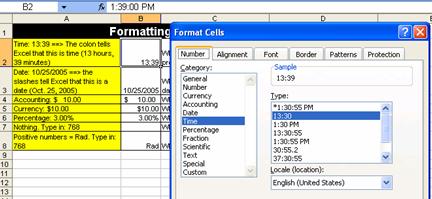

23. Ctrl + ~ to

remove formula view. Then click on each cell in column B and using the Format

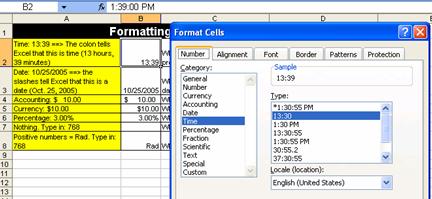

Cells dialog box look at what Number format each cell is using

i.

For Example in Figure 177

you can see that B2 has a time format

Figure 177

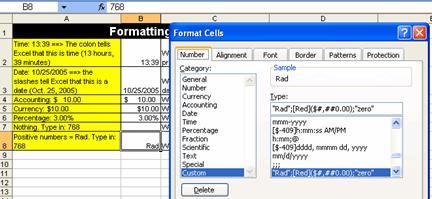

ii.

In Figure 178 you

can see the custom format (discussed in another book):

Figure 178

Rule #19: Cell Formatting is the façade that sits on top of

data and formulas. What you see is not always what sits in the cell.

The next page reminds you that there are six tabs in the

Formatting Cells dialog box. Two pages ahead we have an example of the

formatting façade getting in the way of accurate calculations!

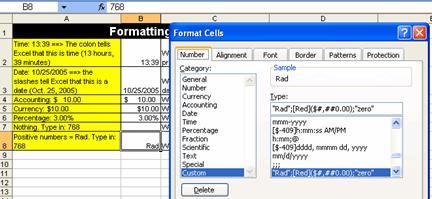

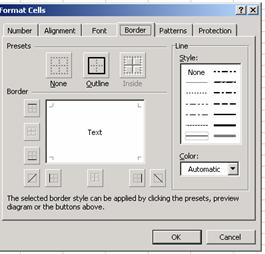

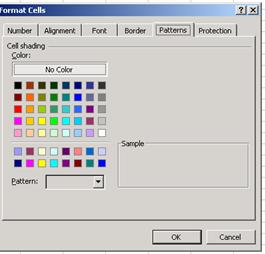

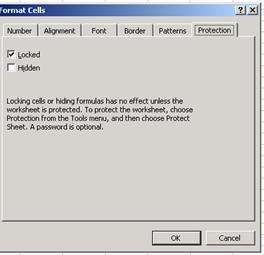

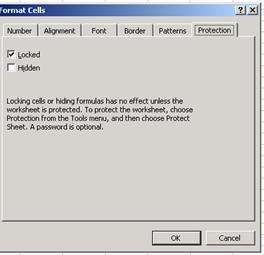

Make a note that there are six tabs in the Format Cells

dialog box as seen below (Figure 179):

Figure 179

Here are the steps to

learn how to use the ROUND Function in Excel to insure accurate payroll

calculations when rounding to the penny is required

1)

Navigate to the sheet named “Round for Deduction”.

Before you make any calculations on this sheet, follow the calculations in step

2 and make the deduction calculations by hand with a pencil.

2)

How to use a formula to calculate a tax deduction

1.

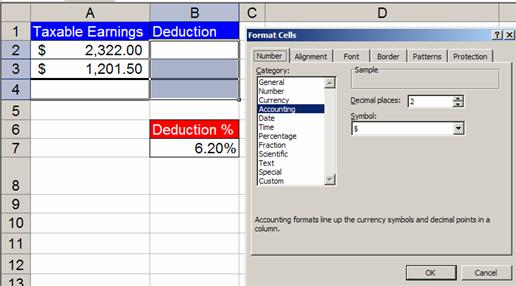

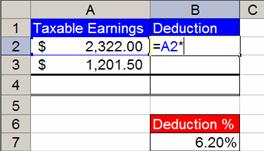

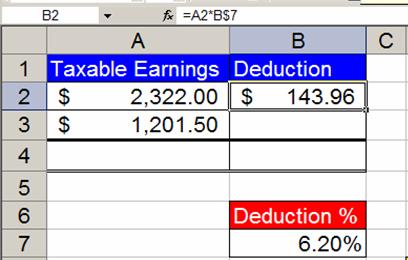

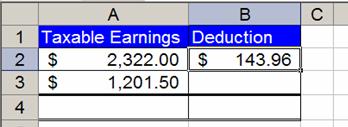

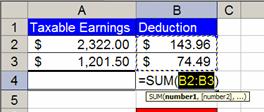

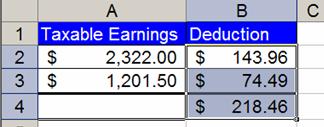

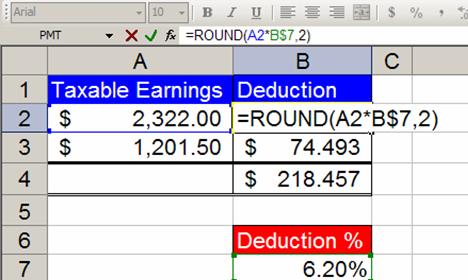

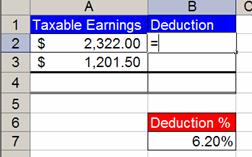

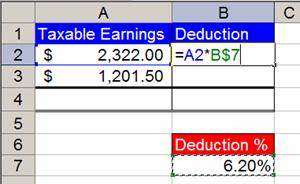

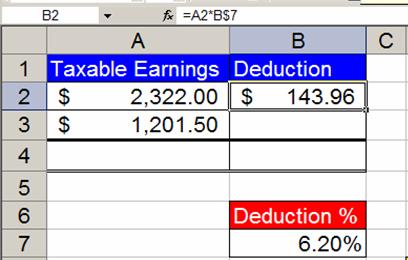

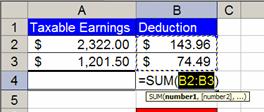

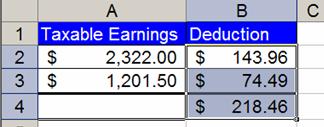

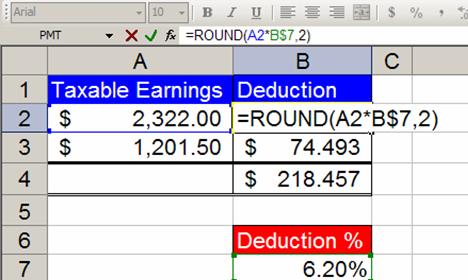

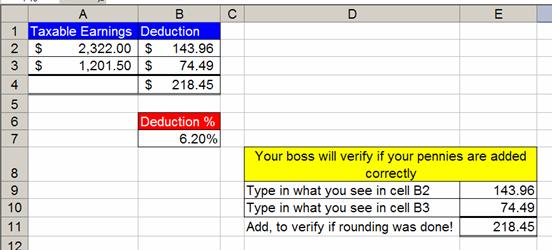

Figure 180 shows

the Taxable earnings and short description of how to calculate a deduction. Use

Figure 181 to make a calculation by hand

using a pencil, an eraser and the rules of rounding to a penny!

Figure 180

Figure 181

3)

Now we can try it in Excel

4)

How to use a formula to calculate a tax deduction

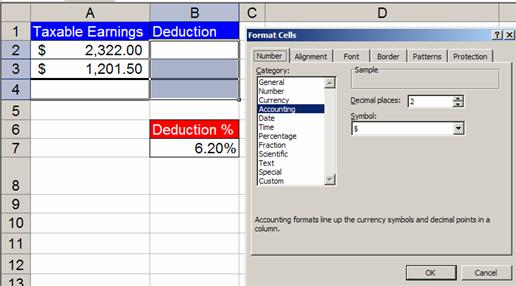

1.

Before we create a formula to calculate the deduction,

let’s look at the Accounting Number format already applied in the cell range

B2:B4. Highlight the range and hold the Ctrl key, then tap the 1 key. You will

see the Format Cells dialog box (Figure 182):

Figure 182

2.

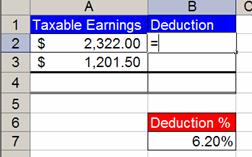

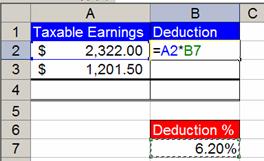

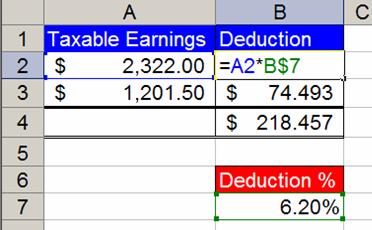

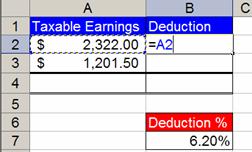

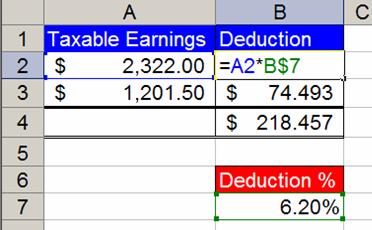

To begin a formula, type the equal sign (Figure 183):

Figure 183

3.

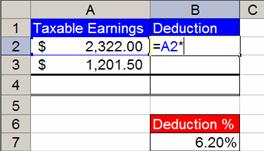

With the thick white cross cursor, click on cell A2

(The cell reference A2 will appear in the formula) (Figure 184):

Figure 184

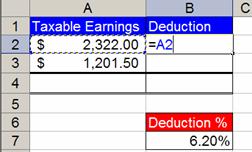

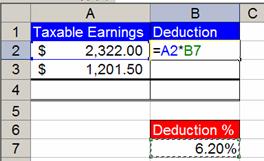

4.

Type the multiplication symbol (Figure 185):

Figure 185

5.

Click on the cell with the deduction % as seen below (Figure

186):

Figure 186

6.

Click the F4 key twice to lock the percent (Figure 187):

Figure 187

7.

Hold the Ctrl key, then tap the Enter key to place the

formula in the cell (Notice that you can still see the formula in the formula

bar (Figure 188):

Figure 188

8.

Point to the fill handle (Little black box in lower

right corner of highlighted cell) (Figure 189):

Figure 189

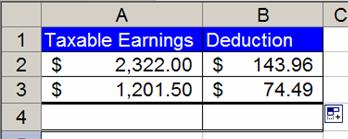

9.

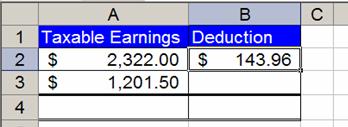

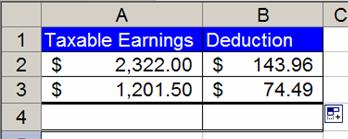

With fill handle selected, copy formula from B2 to B3 (Figure

190):

Figure 190

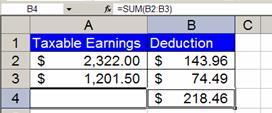

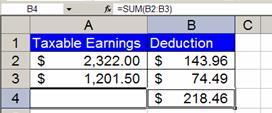

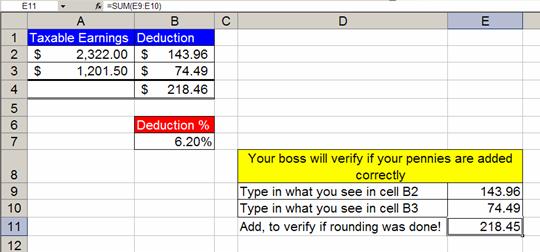

10. In

cell B4 add a SUM function by holding the Alt key and tapping the equal sign.

Verify that the SUM function selected the correct cells (Figure 191):

Figure 191

11. Hold

Ctrl and tap Enter (Figure 192):

Figure 192

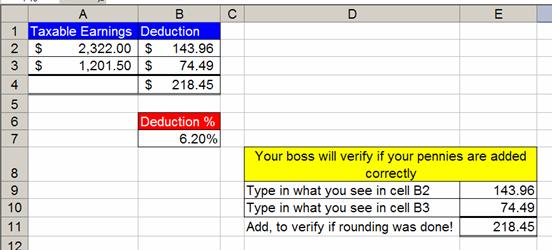

12. Go

down to the area with the yellow instructions and verify that you entered the

correct formula to calculate your payroll deductions. In cells E9 and E10 type

what you see in cells B2 and B3, respectively (DO NOT USE CELL REFERENCES). Create

a SUM function in cell E11 that adds the two cells above. (Figure 193):

Figure 193

13. Question:

What is the problem here???!!?

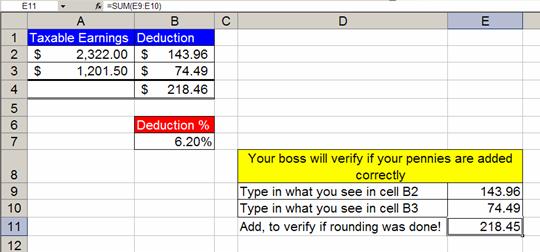

14. Answer:

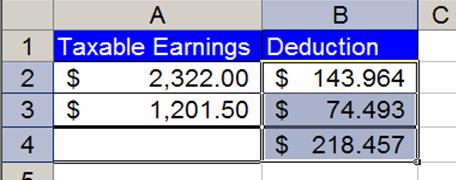

Excel did its part perfectly, but we did not! We forgot to make sure that the

formatting and the calculating formulas are doing the same thing! To see how

these are different, select the cell range B2:B4 and use the increase decimal

button on the formatting toolbar to look at how the Accounting Number format

formats the cells. You should see this after you click the increase decimal

button once (Figure 194):

Figure 194

15. What

has happened here? The formulas underneath have calculated without rounding,

but the formatting on top has made it appear as if it has been rounded. The SUM

function does not look at formatted numbers, but instead looks at the calculated

unrounded numbers.

16. The

solution is to make the format and the calculated numbers exactly the same by

using the ROUND function.

17. Click

the Decrease Decimal button to restore the format. You should see this (Figure 195):

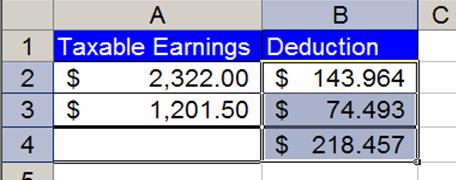

Figure 195

18. Add

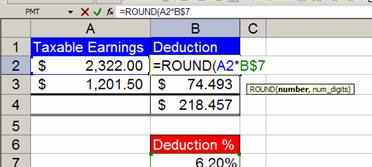

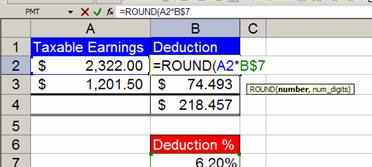

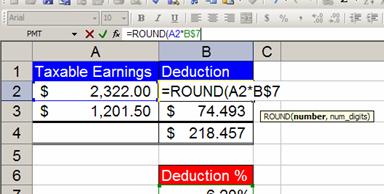

a ROUND function to our formula by clicking in cell B2. To edit the formula

click the F2 keyboard button. You will see this (Figure 196):

Figure 196

19. With

your cursor point in between the equal sign and the letter “A” and click to

insert your cursor into the formula. Then type the letters and characters

“ROUND(“ as seen here (Figure 197):

Figure 197

20. Then

point your cursor to the formula bar and click at the end of the formula as

seen here (Figure 198):

Figure 198

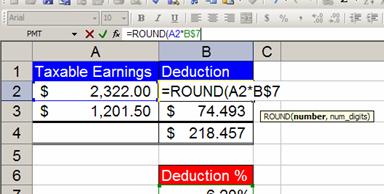

21. Type

the characters and numbers: “,2)” as seen here (Figure 199):

Figure 199

22. Hold

the Ctrl key and then tap the Enter key. Then copy the formula to cell B3. Now

you are done and you should see this (Figure 200):

Figure 200

5)

Conclusions: because formatting (such as currency)

is like a façade that sits on top of the number, when you have a formula that

has the potential to yield more decimal places than the format displays, use

the ROUND function.

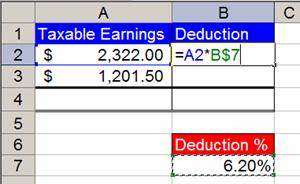

1.

For a payroll calculation that must be rounded to the

penny, instead of =A2*B$7, use =ROUND(A2*B$7,2); where the second argument “2” means round to the second

decimal.

2 means round to the penny (Payroll)

0 means round to the dollar (Income Taxes)

-3 means round to the thousands position. (Financial

Statements)

Rule #20:

Because formatting (such as currency) is like a façade that sits on top of the

number, when you have a formula that has the potential to yield more decimal

places than the format displays, use the ROUND function.

Next we will look at how to work with Date formatting.

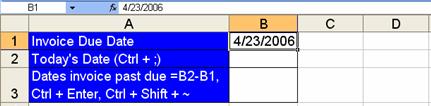

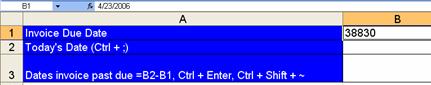

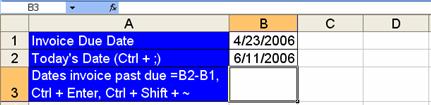

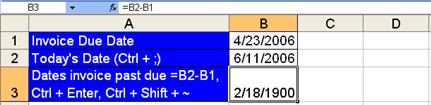

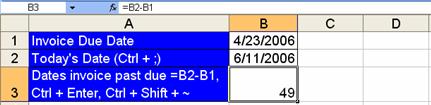

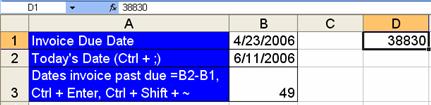

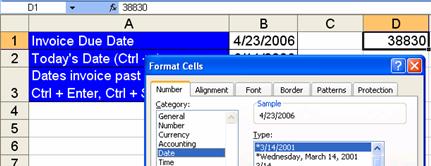

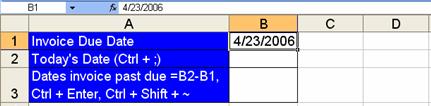

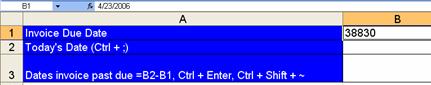

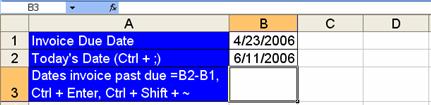

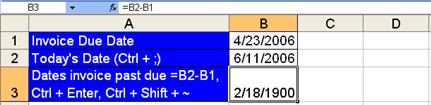

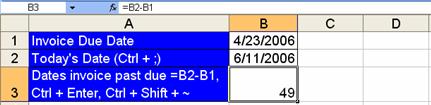

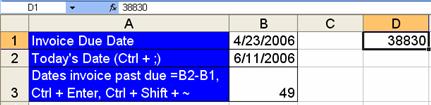

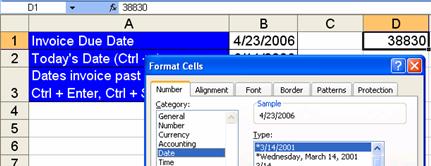

With Date format, Excel sees the

number of days since January 1, 1900 (inclusive). For example: January 1, 1900 is

represented by the serial number 1; January 2, 1900 is represented by the

serial number 2; and April 23, 2006 is represented by the serial number 38,830.

Here are the steps to

learn how to understand the Date format and to make date calculations (Excel

date math)

1. Navigate

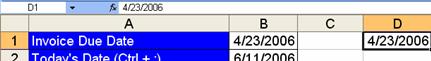

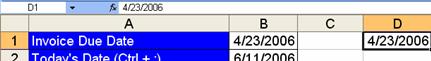

to the sheet named “Date Math”. You should see this (Figure 201):

Figure 201

2. Hold

Ctrl and tap on the ~ key (this reveals what is actually in the cell; this is

called formula view). You should see what is in Figure 202. Understanding the Date format requires that you know that when

you type “4/23/2006” (Figure 201), Excel

sees 38830 (Figure 202). The “4/23/2006”

is the façade that we see. The 38830 is the serial number that Excel sees. This

serial number is very useful for making date calculations…

Figure 202